Yesterday I gave a talk at a meeting of the Society of Bookbinders in Taunton. The theme was ‘Twenty bindings across fifty years’ – showing a progression from no skill, no tools and no design ideas to something at least satisfying.

Taunton is 75 miles away so I checked the traffic reports and was warned of possible delays on the Motorway, so I left in a bit of a hurry, taking three boxes of books but leaving one behind that contained three of my earliest bindings. Aaaaargh!! So this post is to fill in that gap.

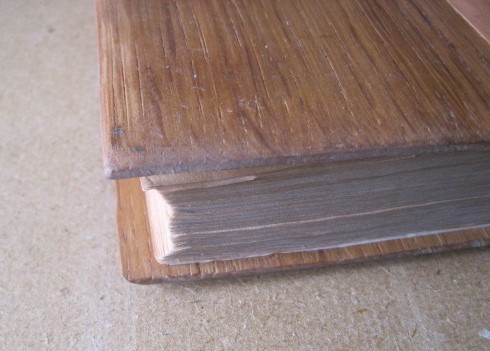

The first binding I intended to show was to highlight the ‘no skills, no tools’ point:

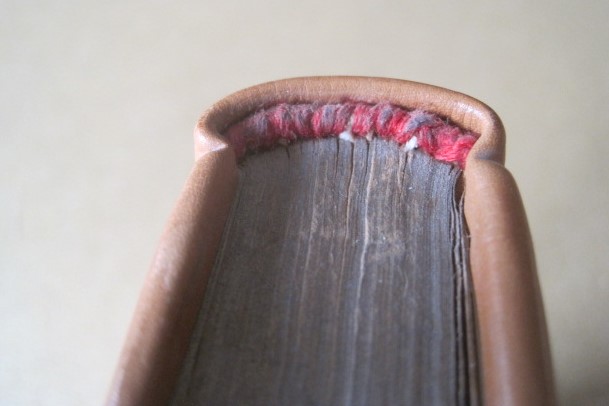

A small Book of Psalms, from the Temple Bible series, re-bound in a piece of plain calf over oak boards made with simple woodworking tools (handsaw, hand drill, rasp, sandpaper). Clumsy headband, ‘squares’ not even. But it does work as a readable book.

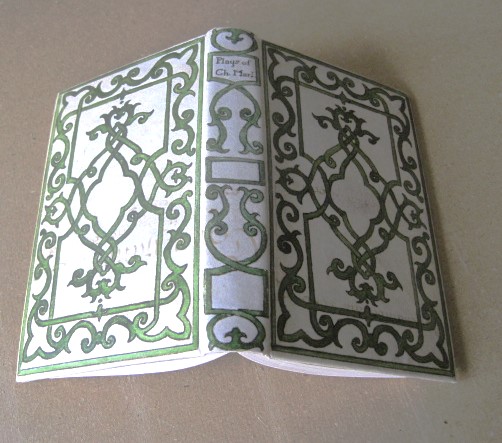

Next, an attempt at decoration without any tools at all:

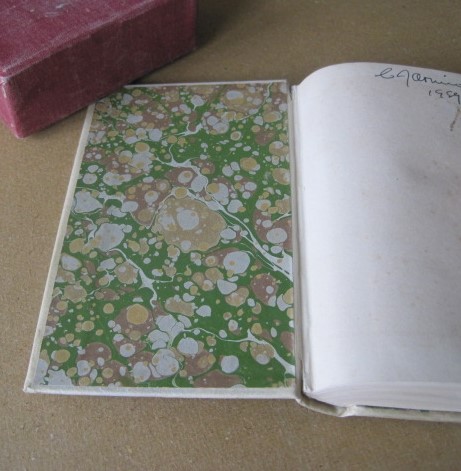

A copy of the World’s Classics edition of the Plays of Christopher Marlowe that I had at school. Original covers re-covered in 1979 in a piece of parchment from a discarded deed. The decoration is copied from an auction catalogue image, drawn in black ink and coloured with gouache watercolour. The marbled paper lining to the covers is not right for the date of the plays. At the time I was very pleased with it.

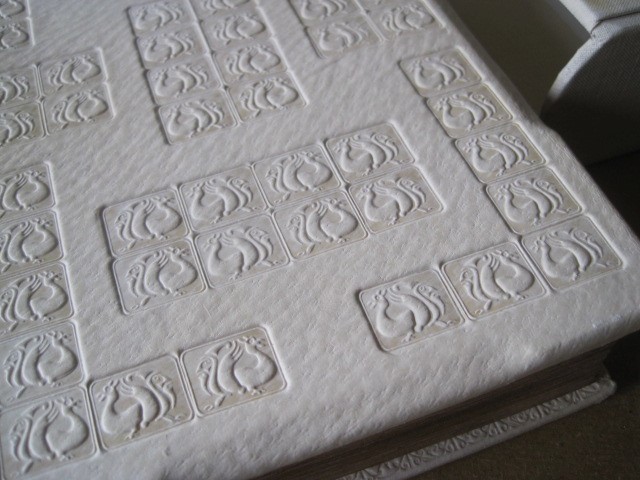

It was five years before I bought my first finishing tools: a pair of ‘grotesque’ stamps made by P & S for me from an image from Gibson’s ‘Early Oxford Bindings’. I used them to decorate the tawed pigskin covers of a copy of Beowulf. Partly bevelled boards, raised double bands, sewn headbands. Matching slipcase in cream bookcloth. I liked it at the time, and I still do. The binding was done in 1980, five years after I started to learn the craft.

Those three books should have been the first part of my talk. Those who heard the rest can now see it here.