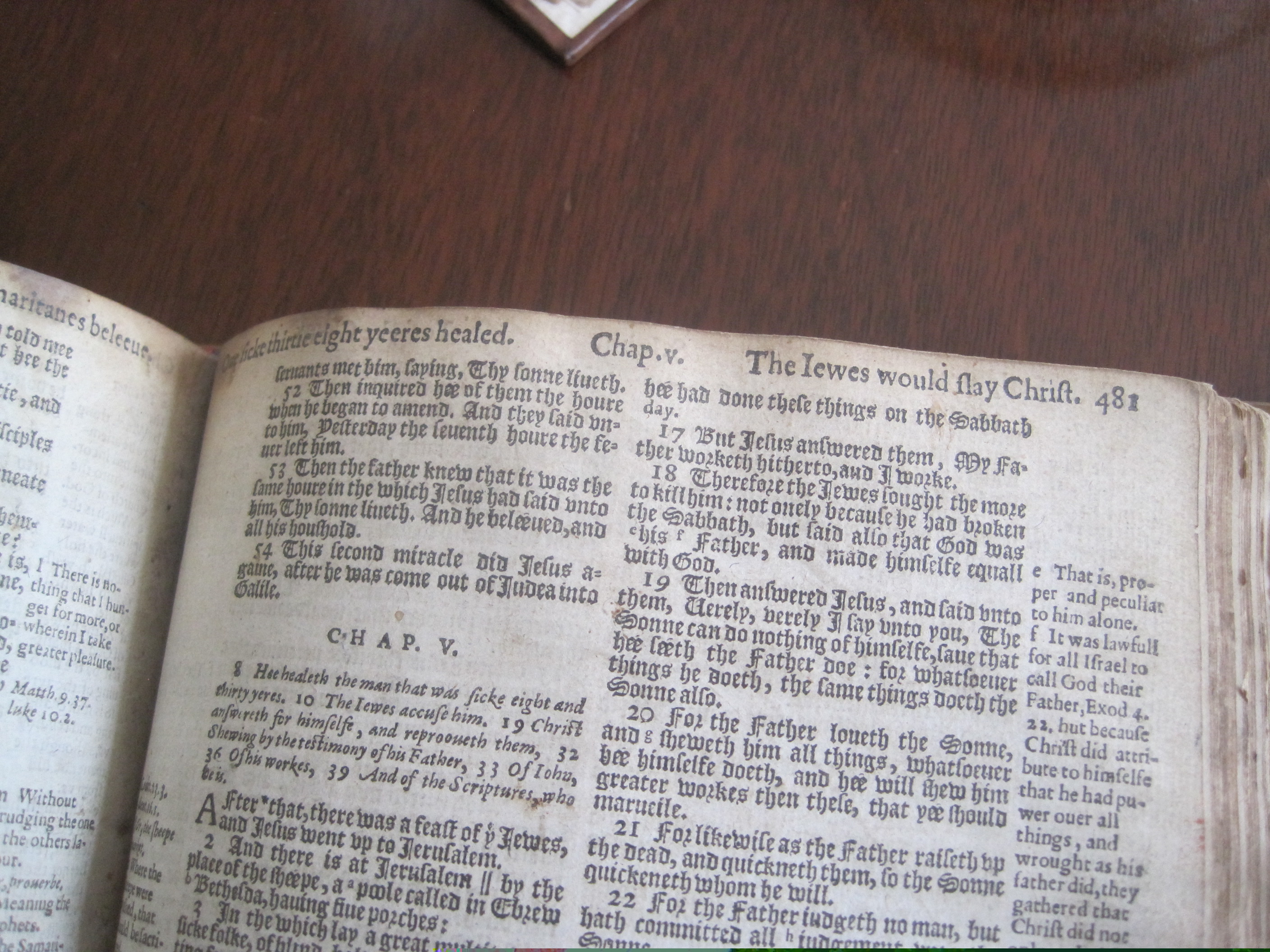

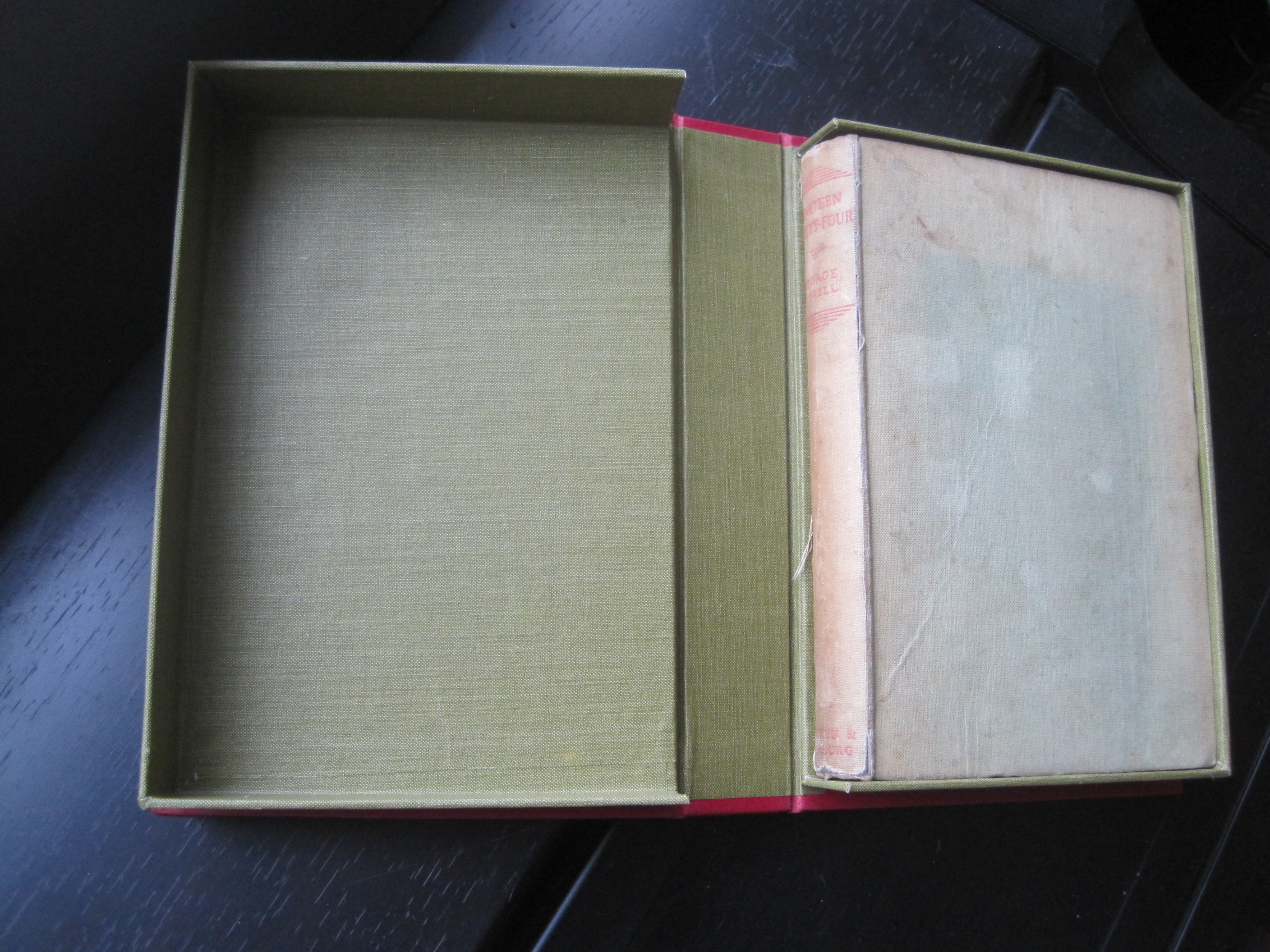

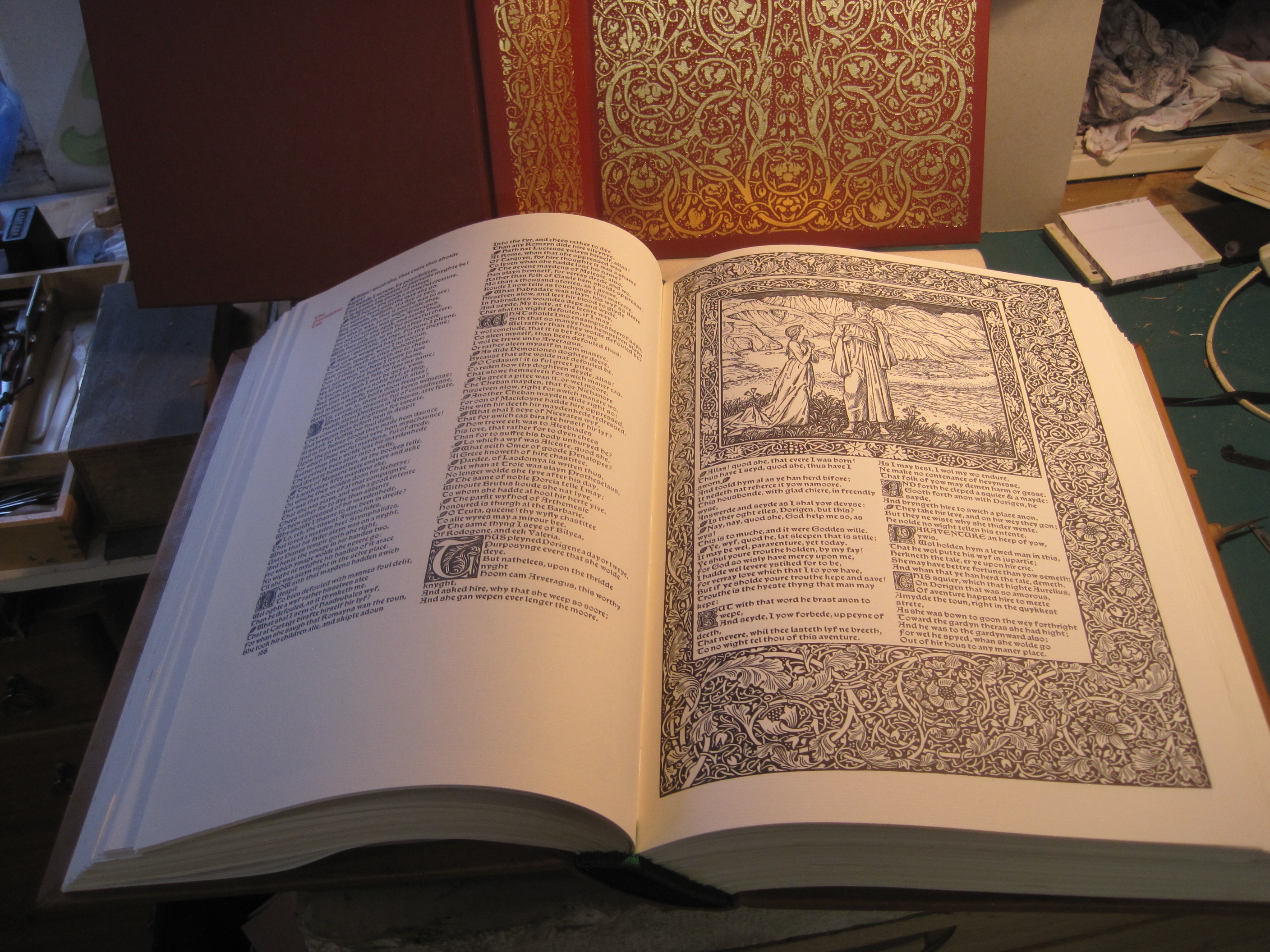

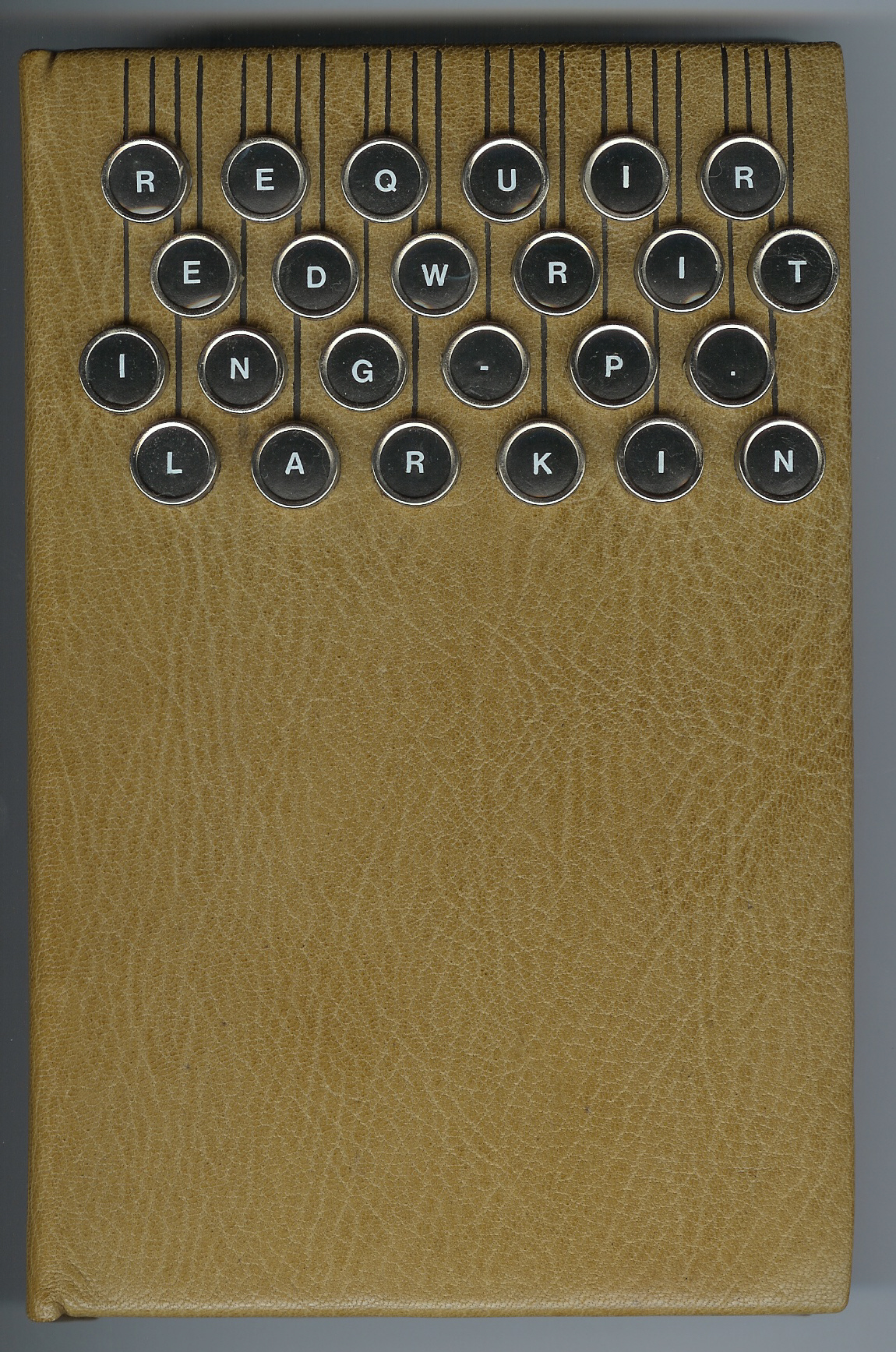

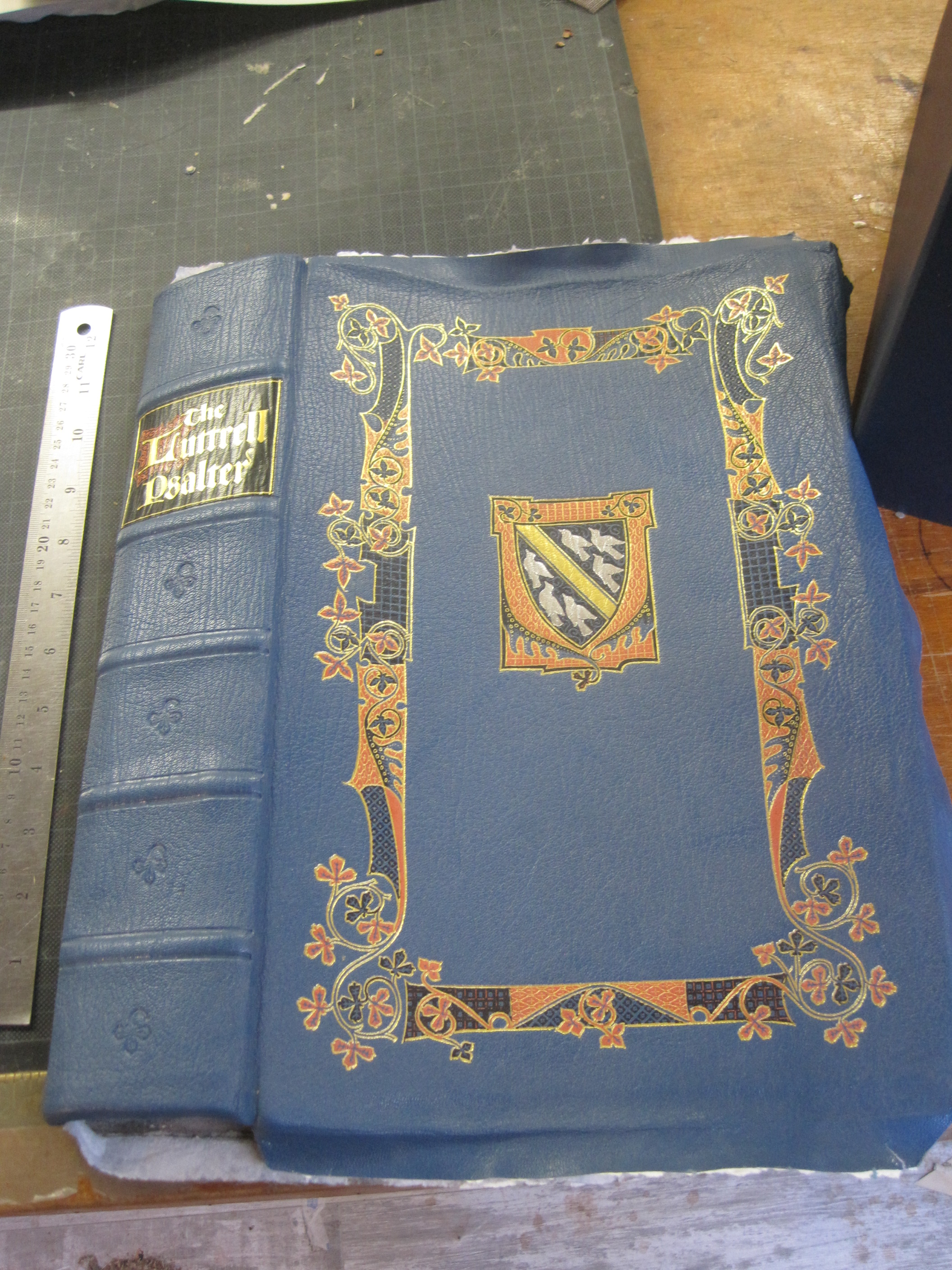

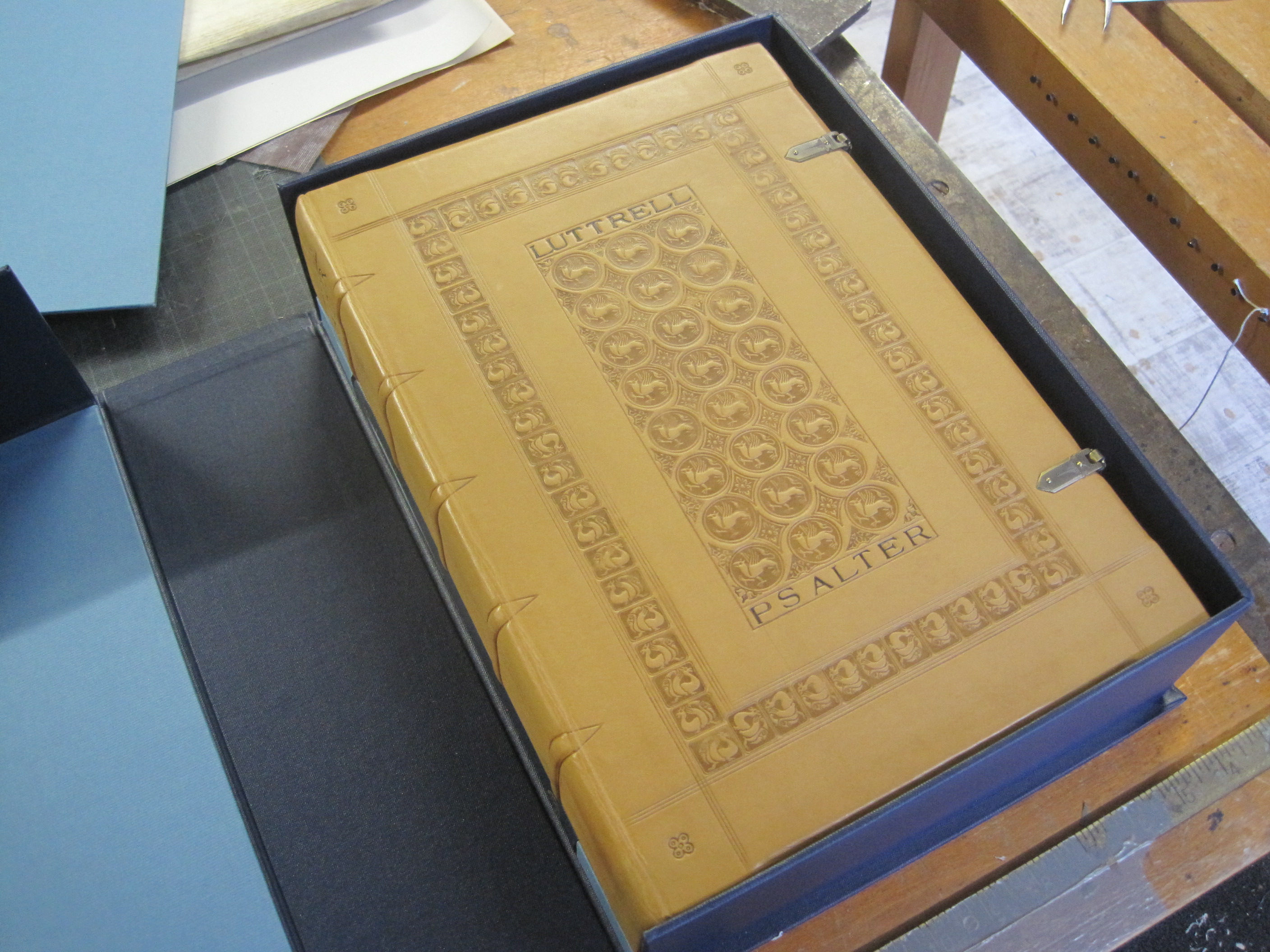

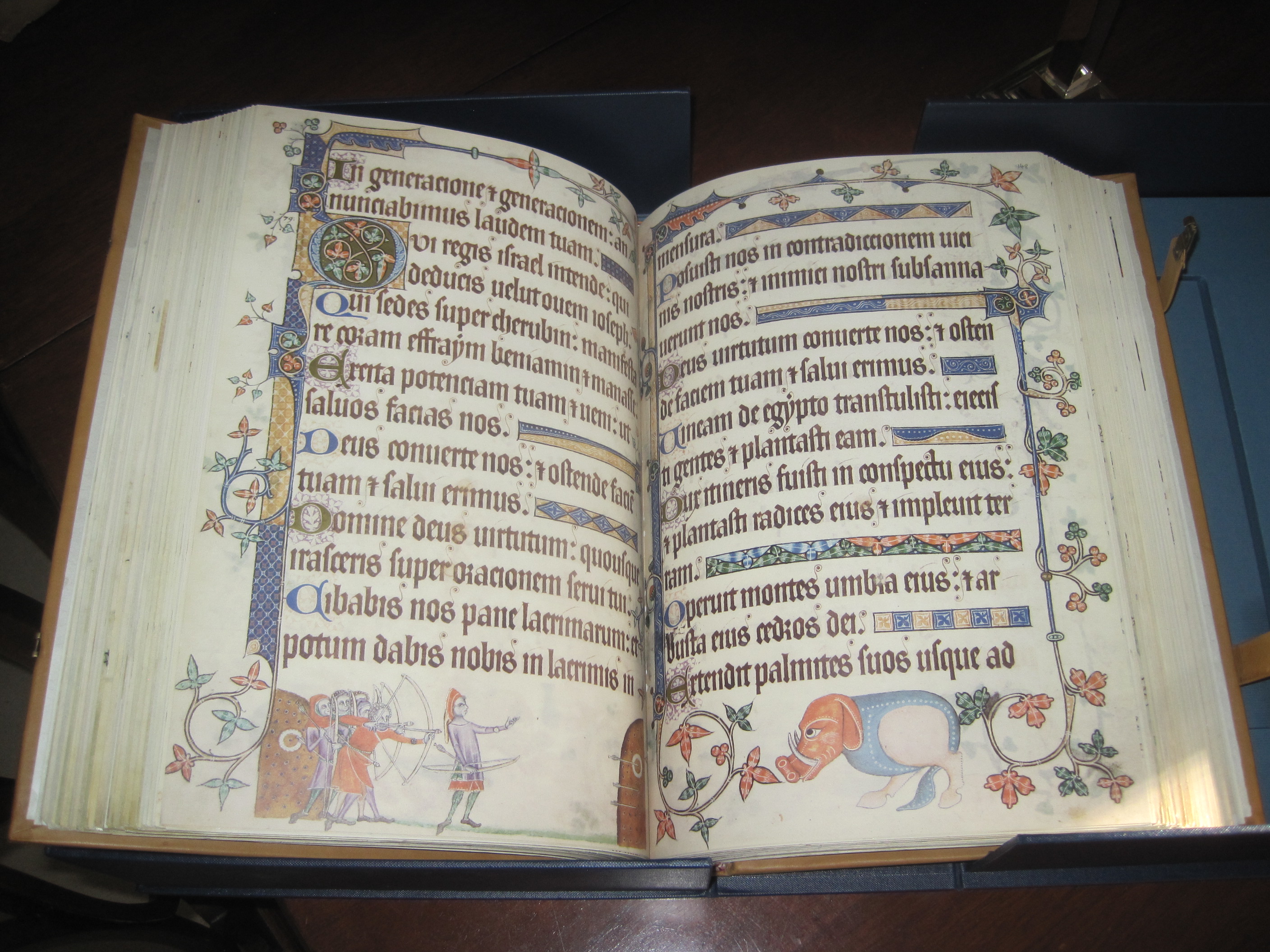

Not THE Luttrell Psalter, of course, but one of the 1480 facsimiles printed for the Folio Society in 2006. I should say straight away that in every respect bar one the book is admirable – exceptional photography of the original in the British Library, excellent scholarly commentary in a separate volume by Michelle P Brown, all contained in a well-made drop-back box. The binding of the facsimile leaves by Smith Settle is strong and sound.

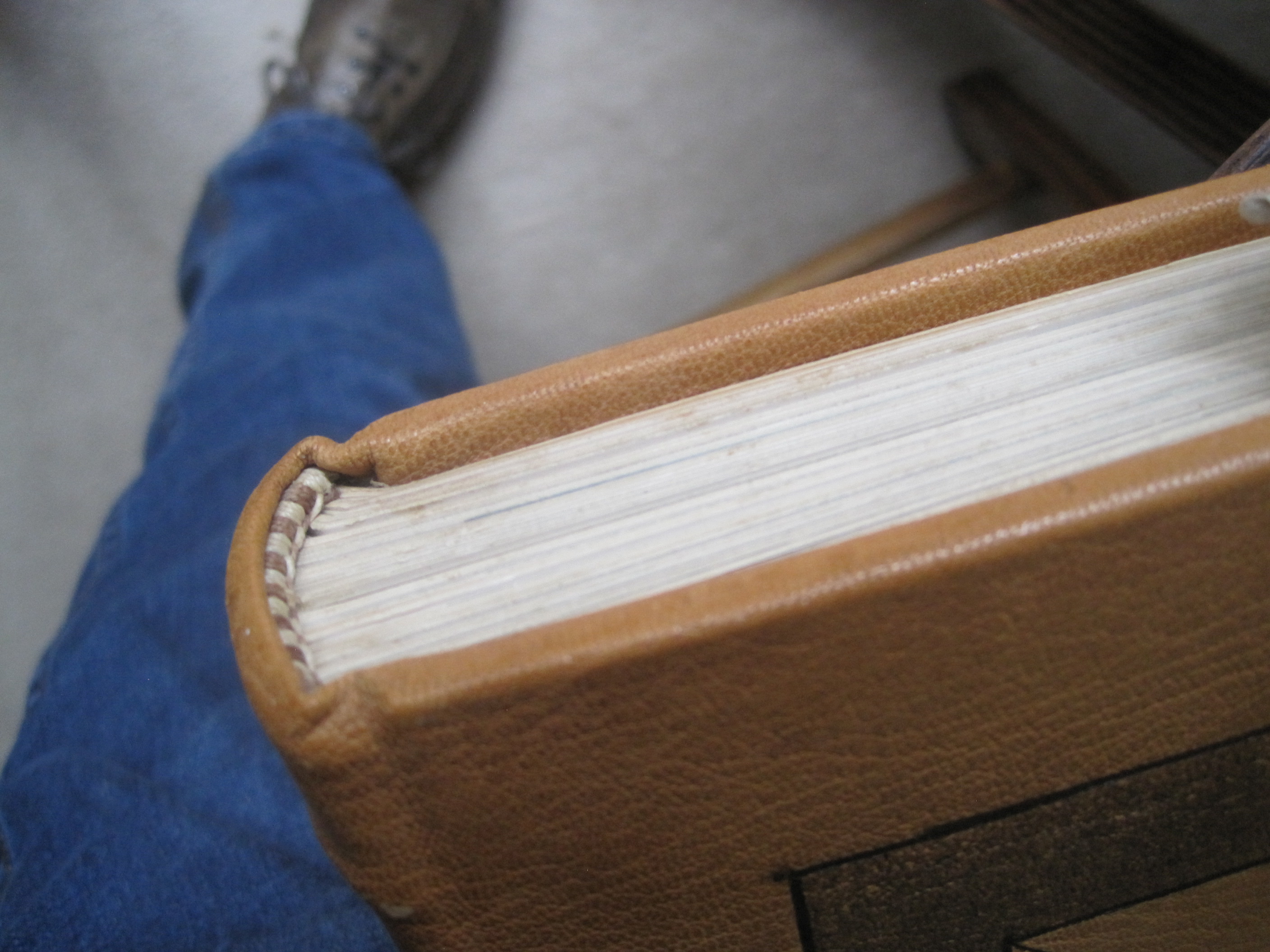

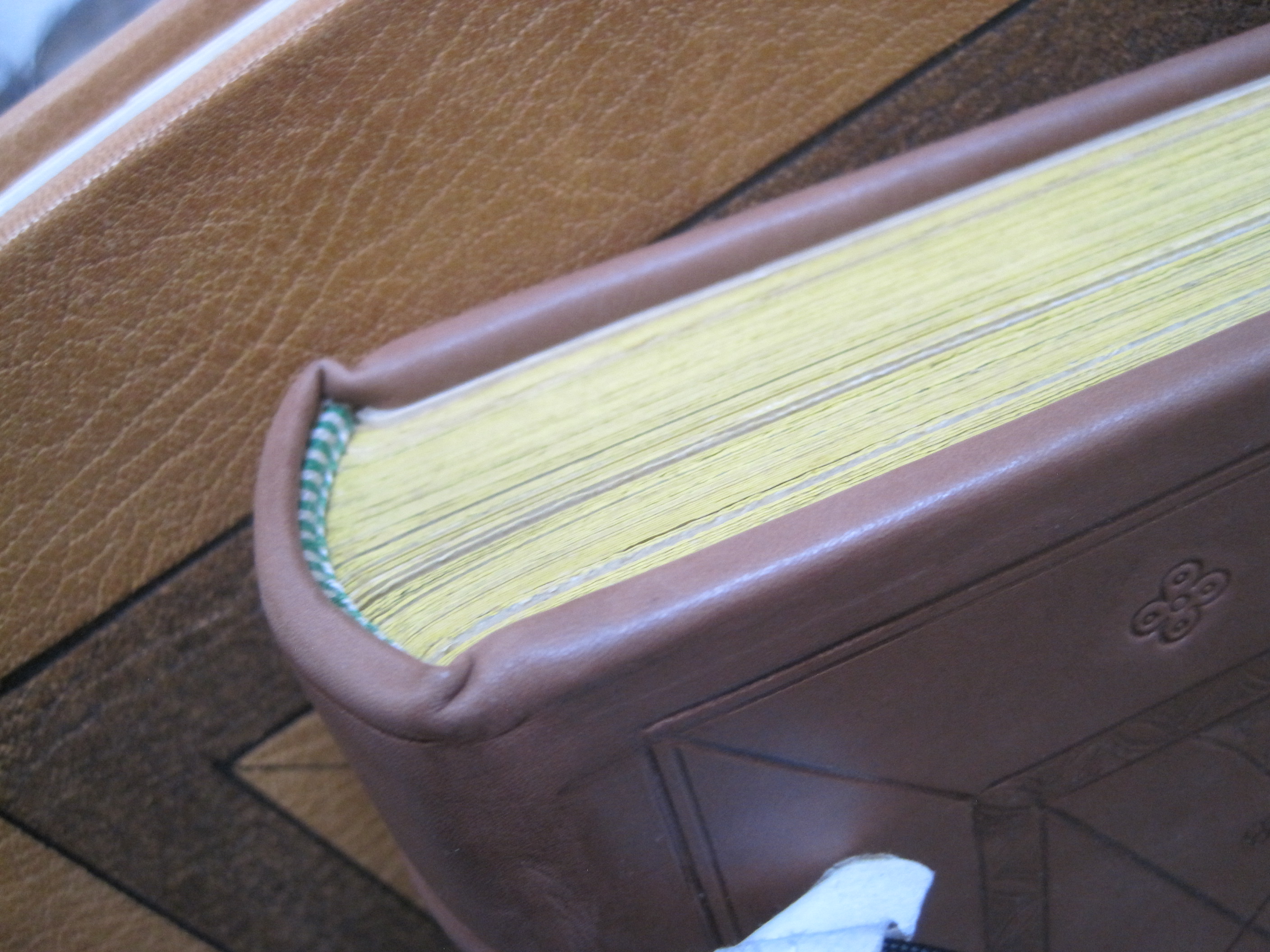

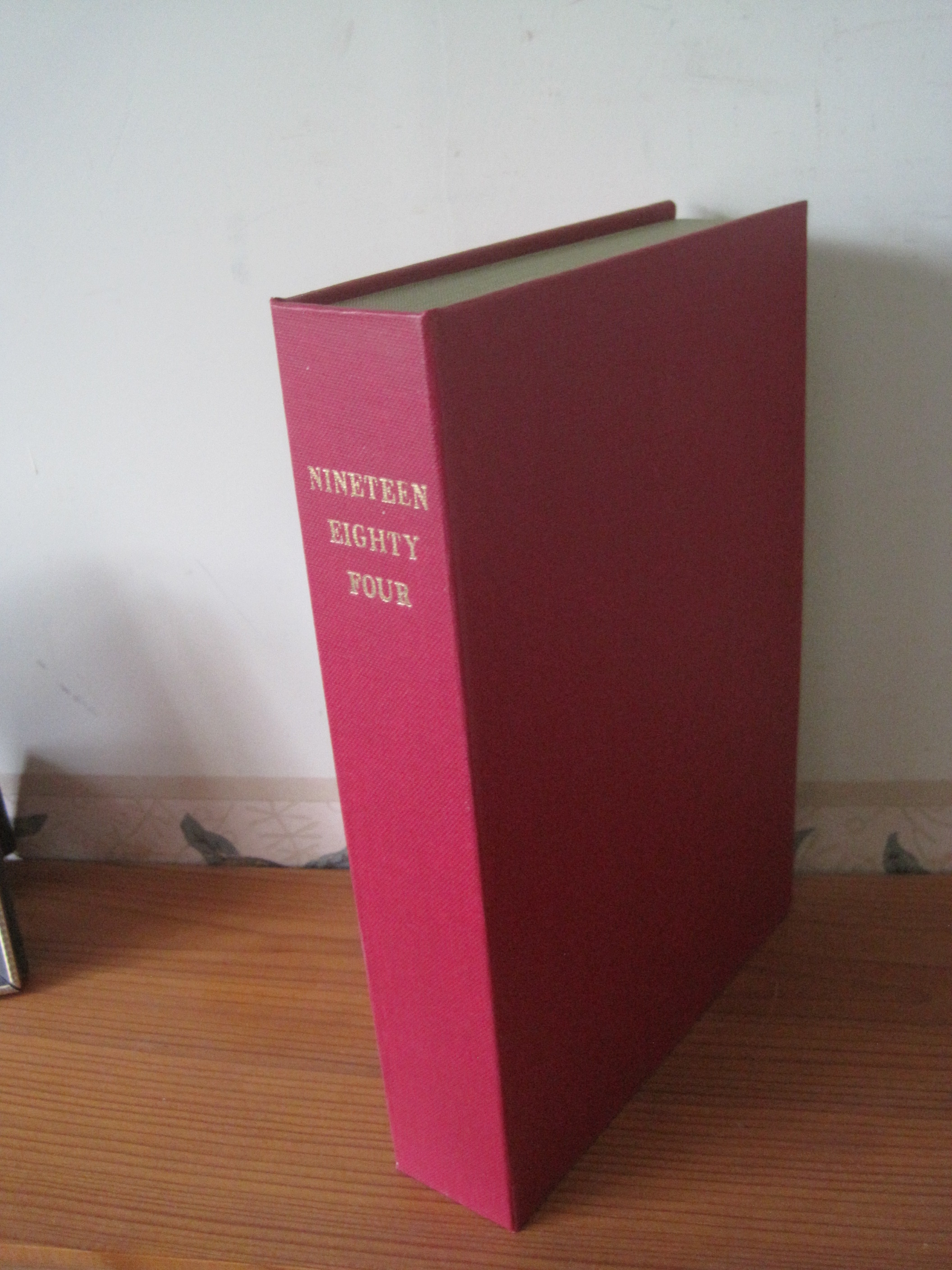

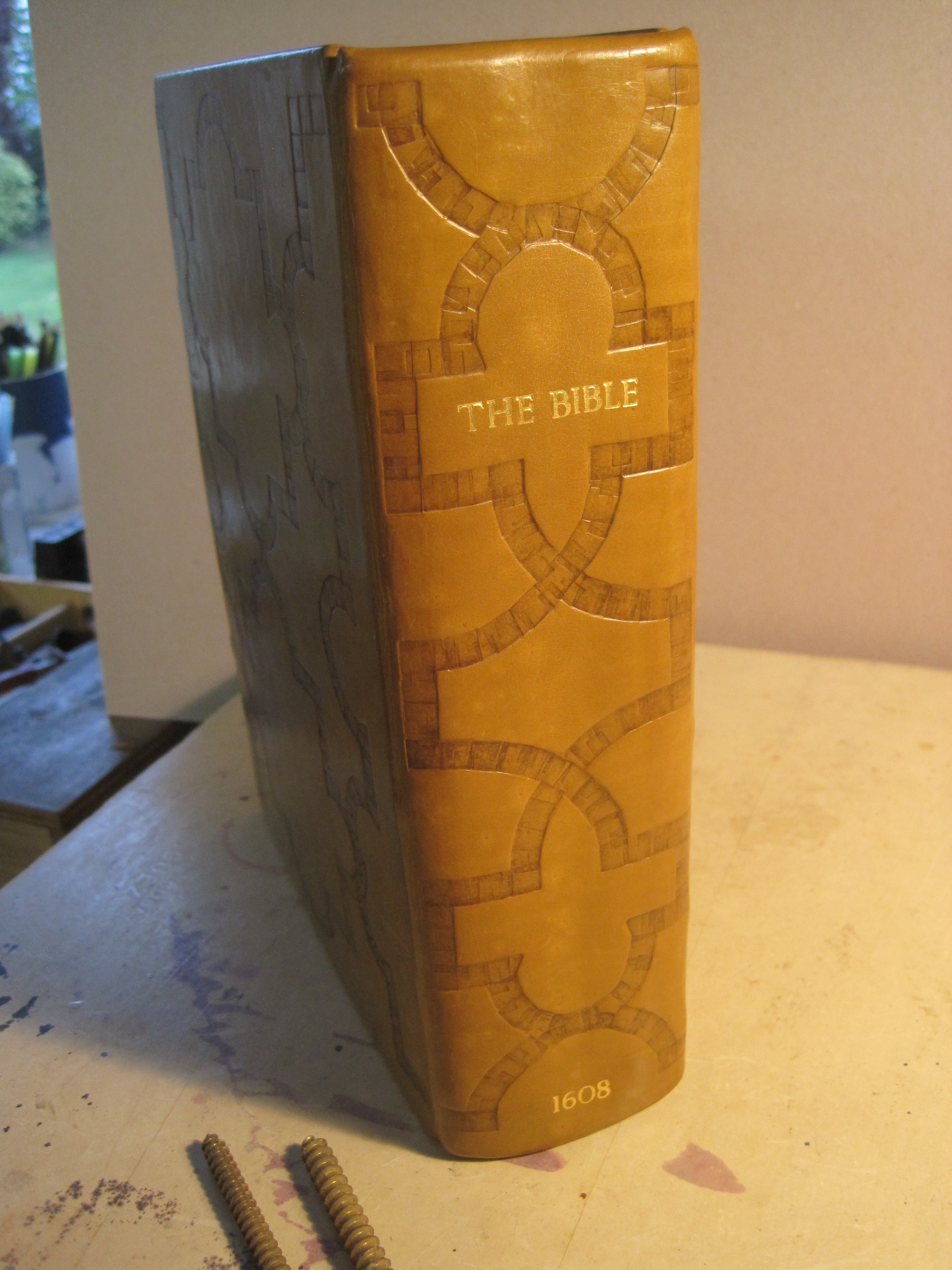

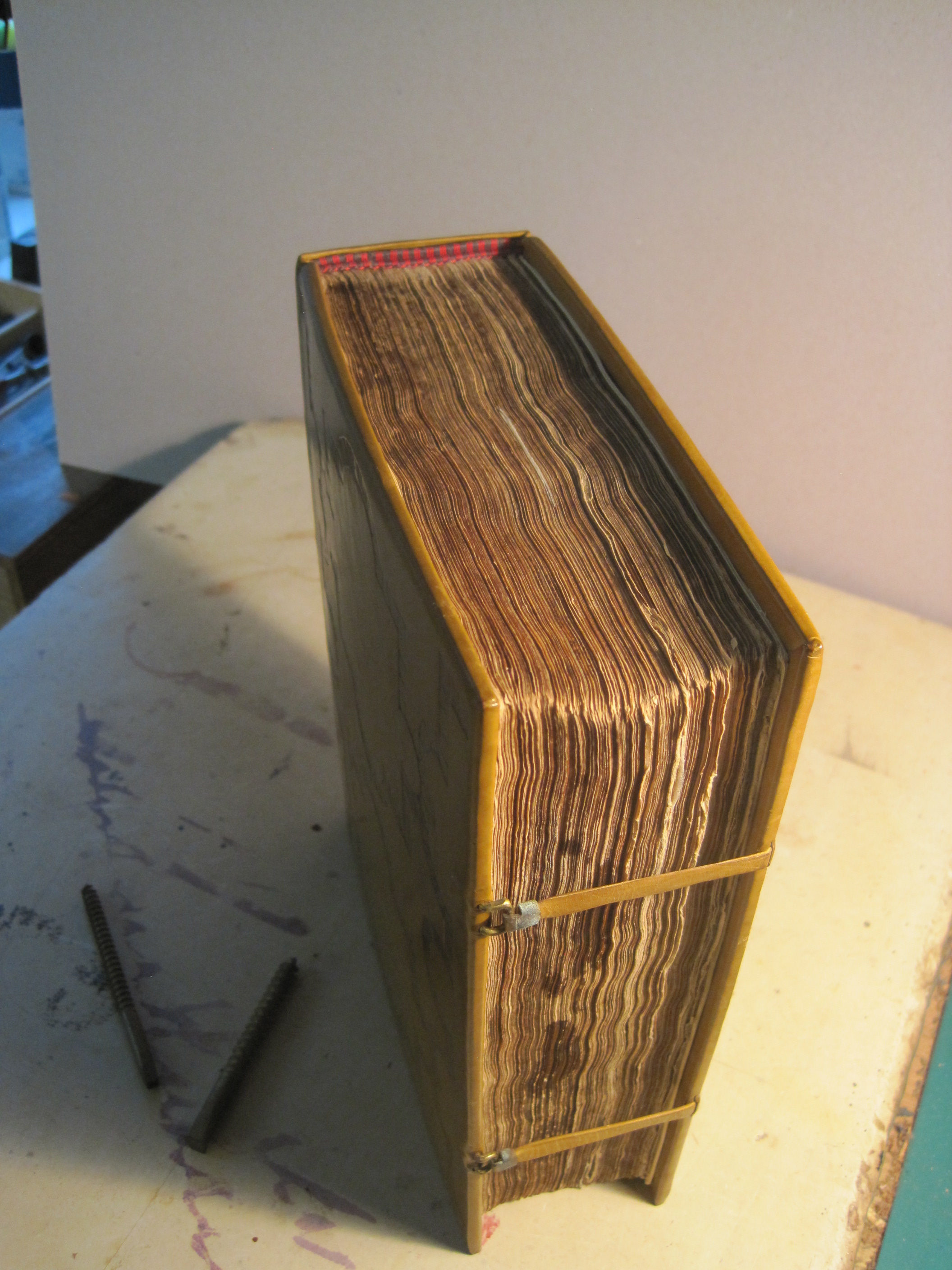

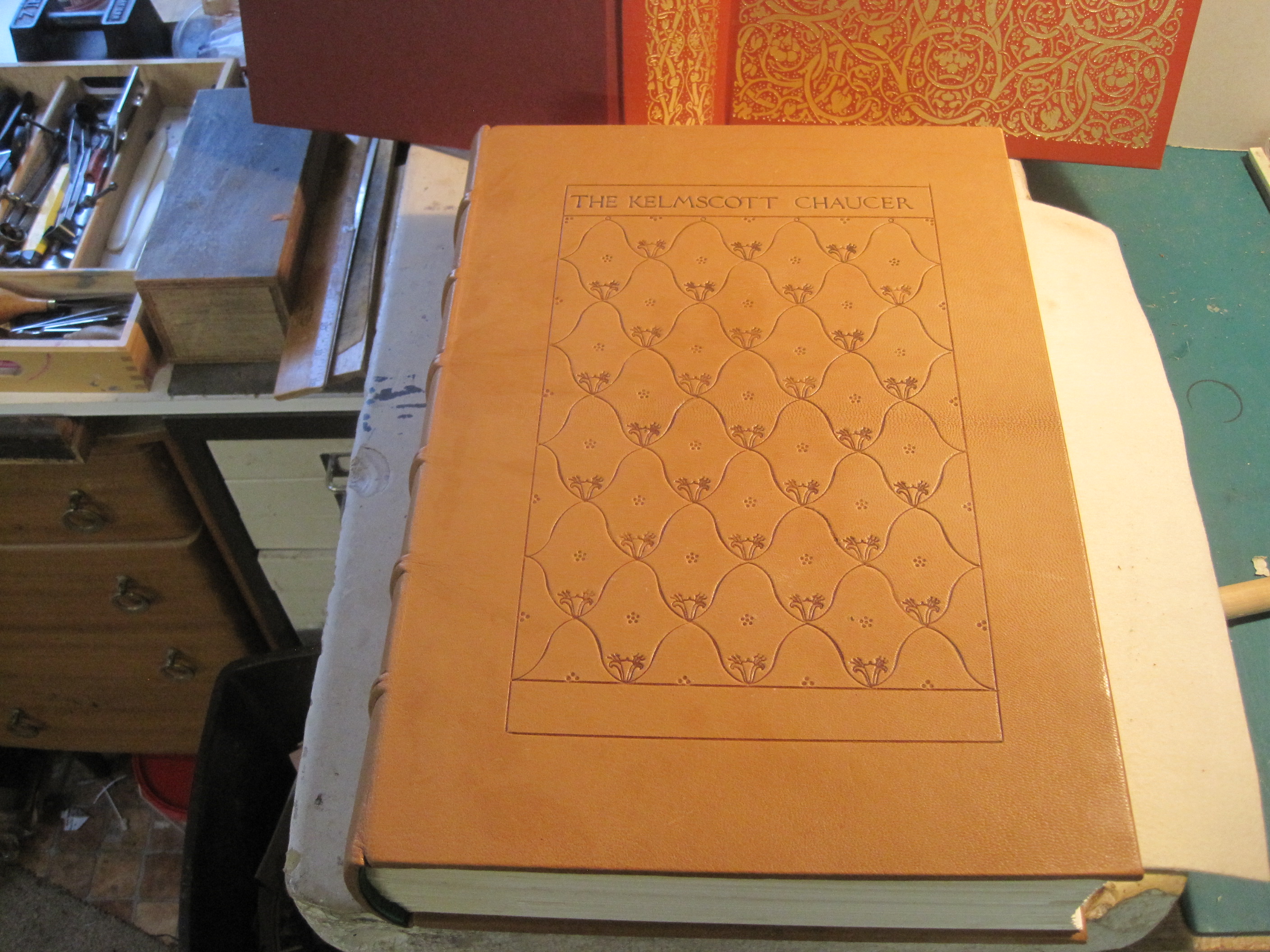

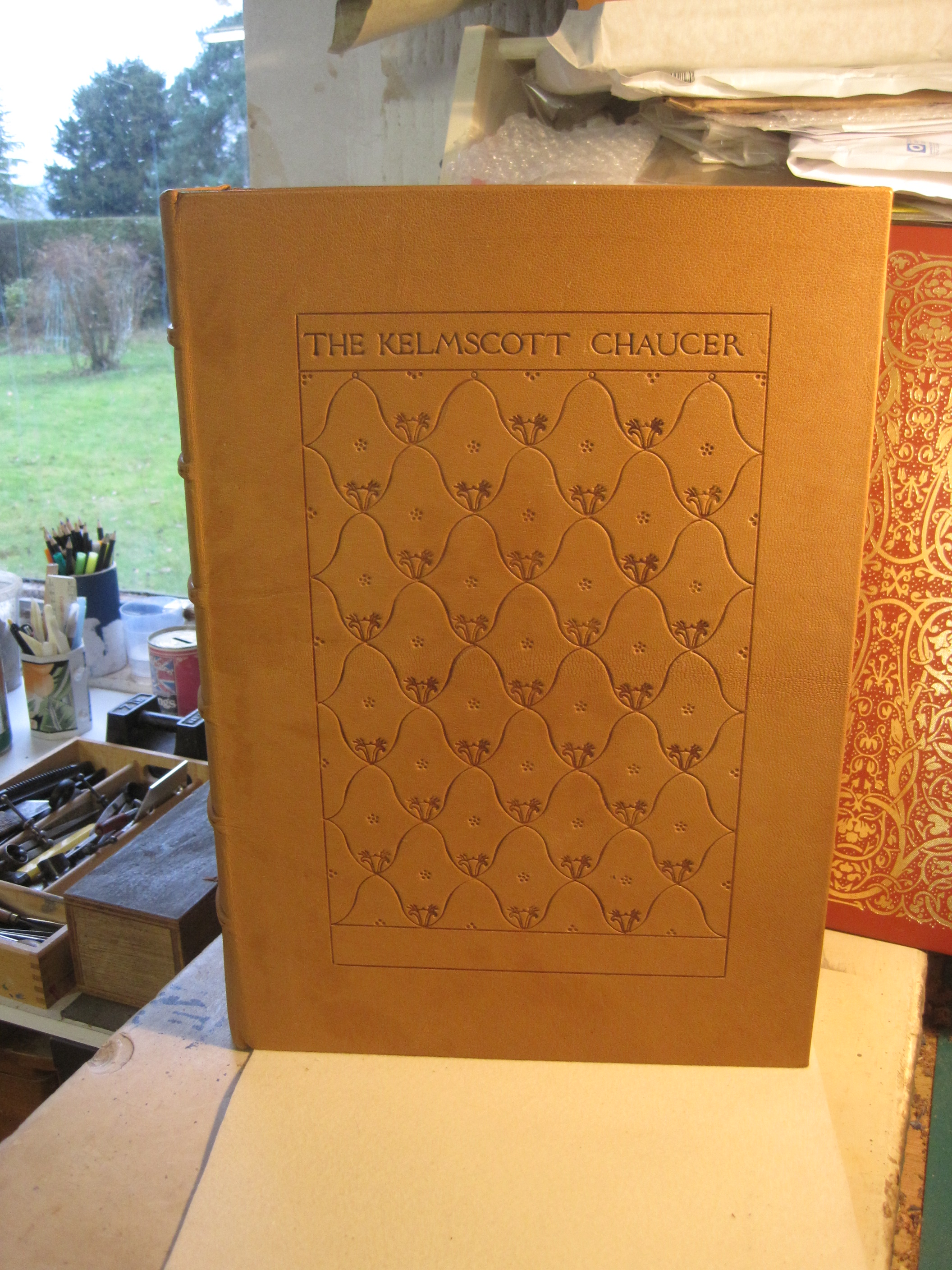

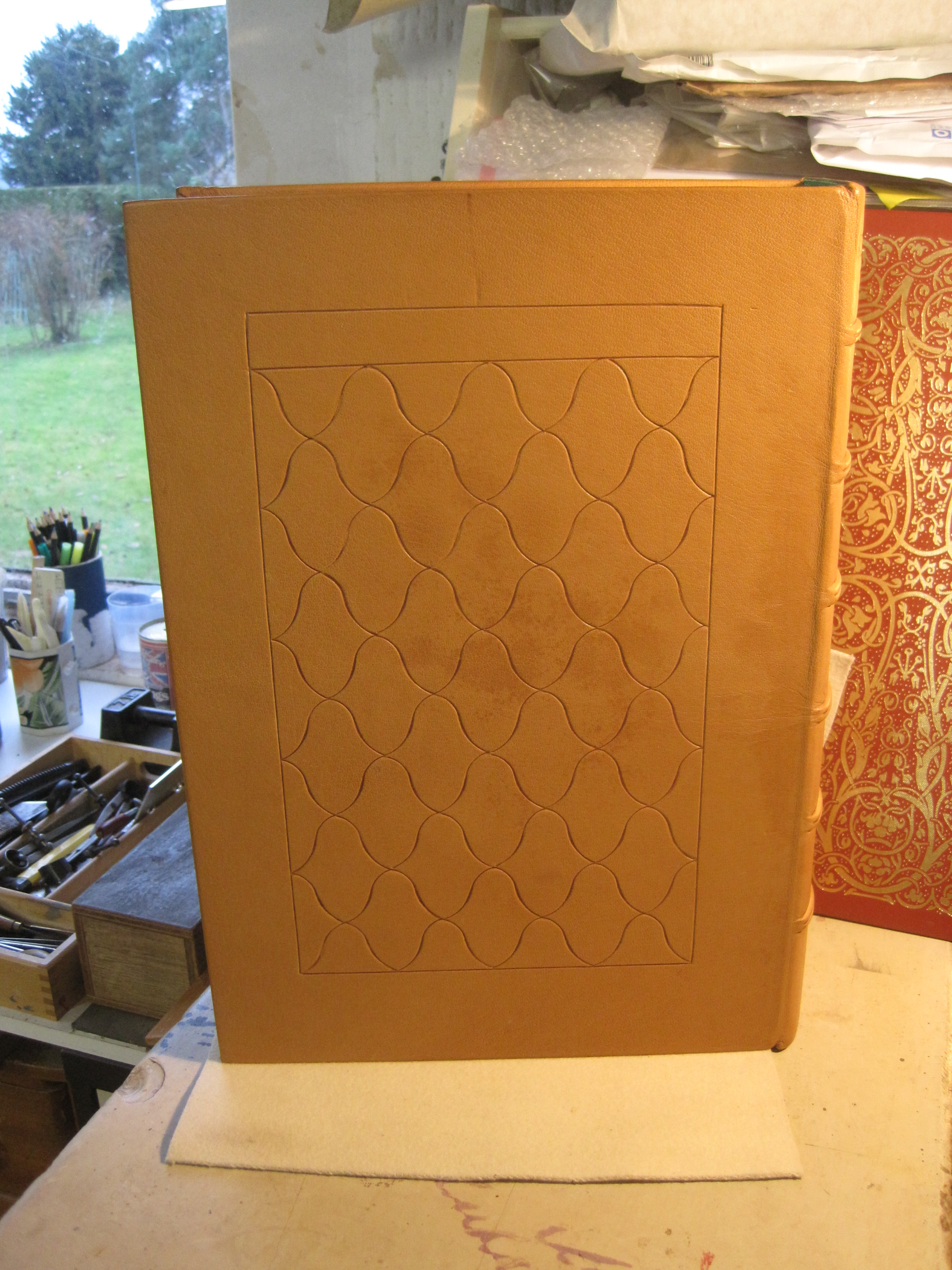

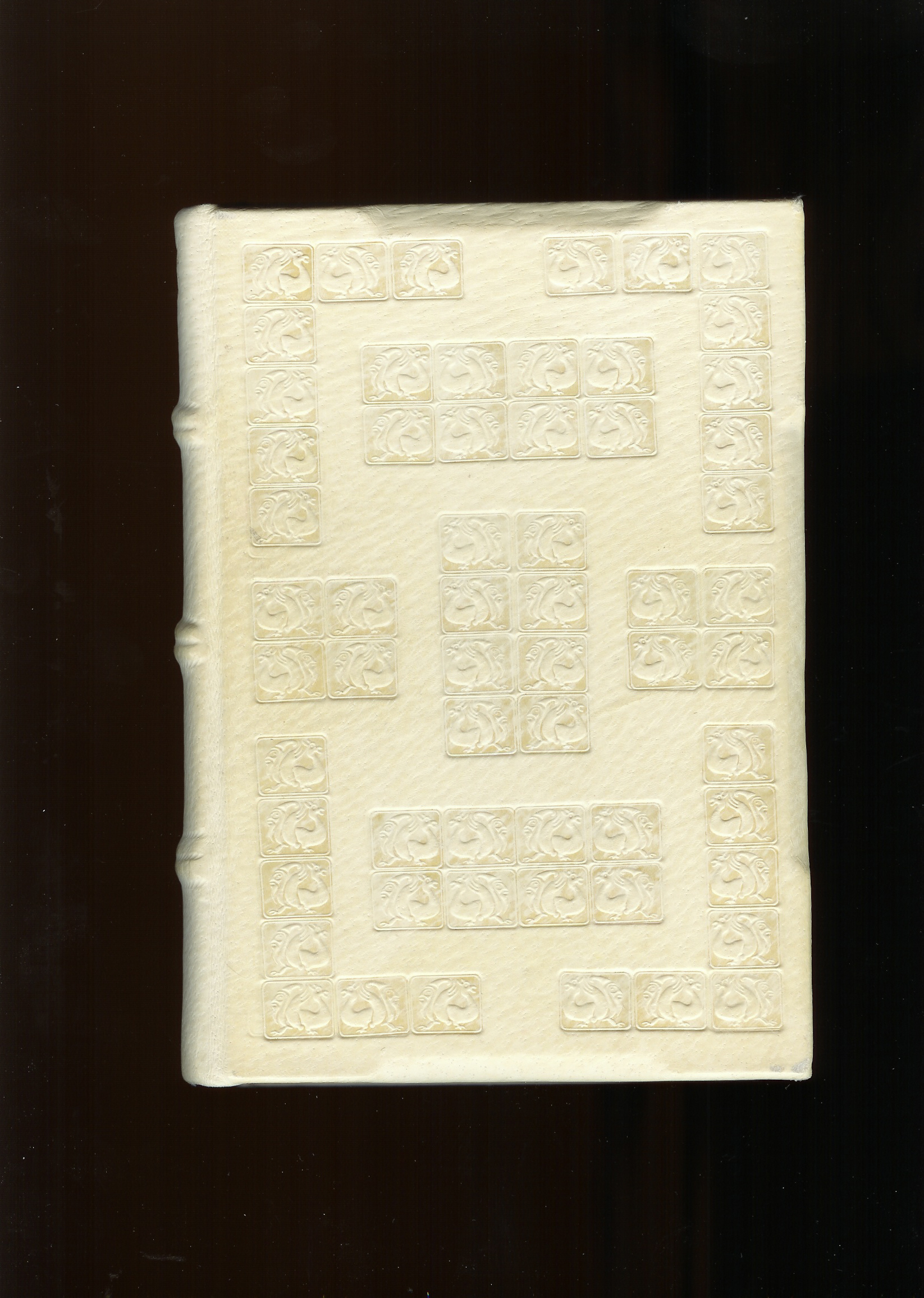

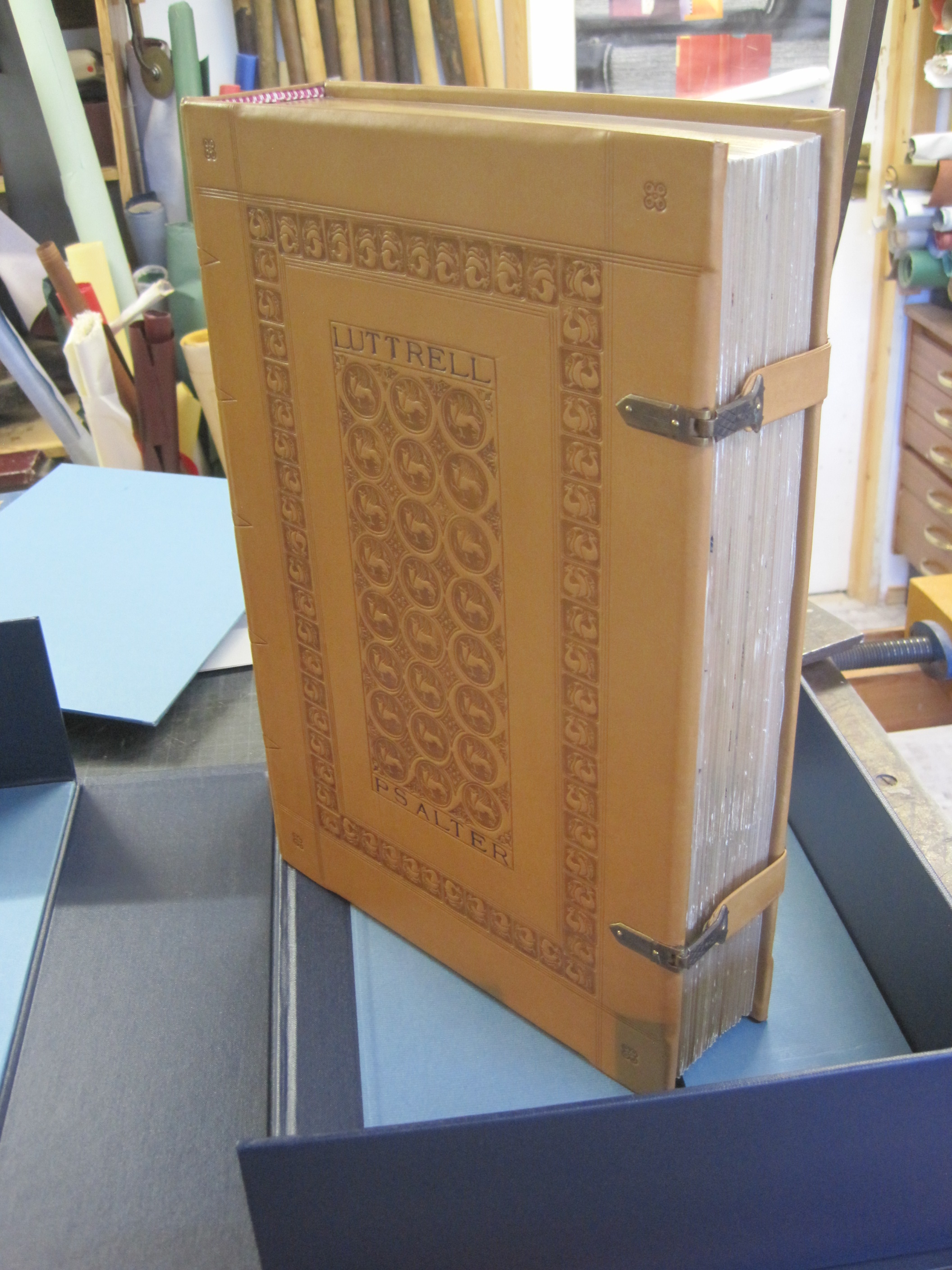

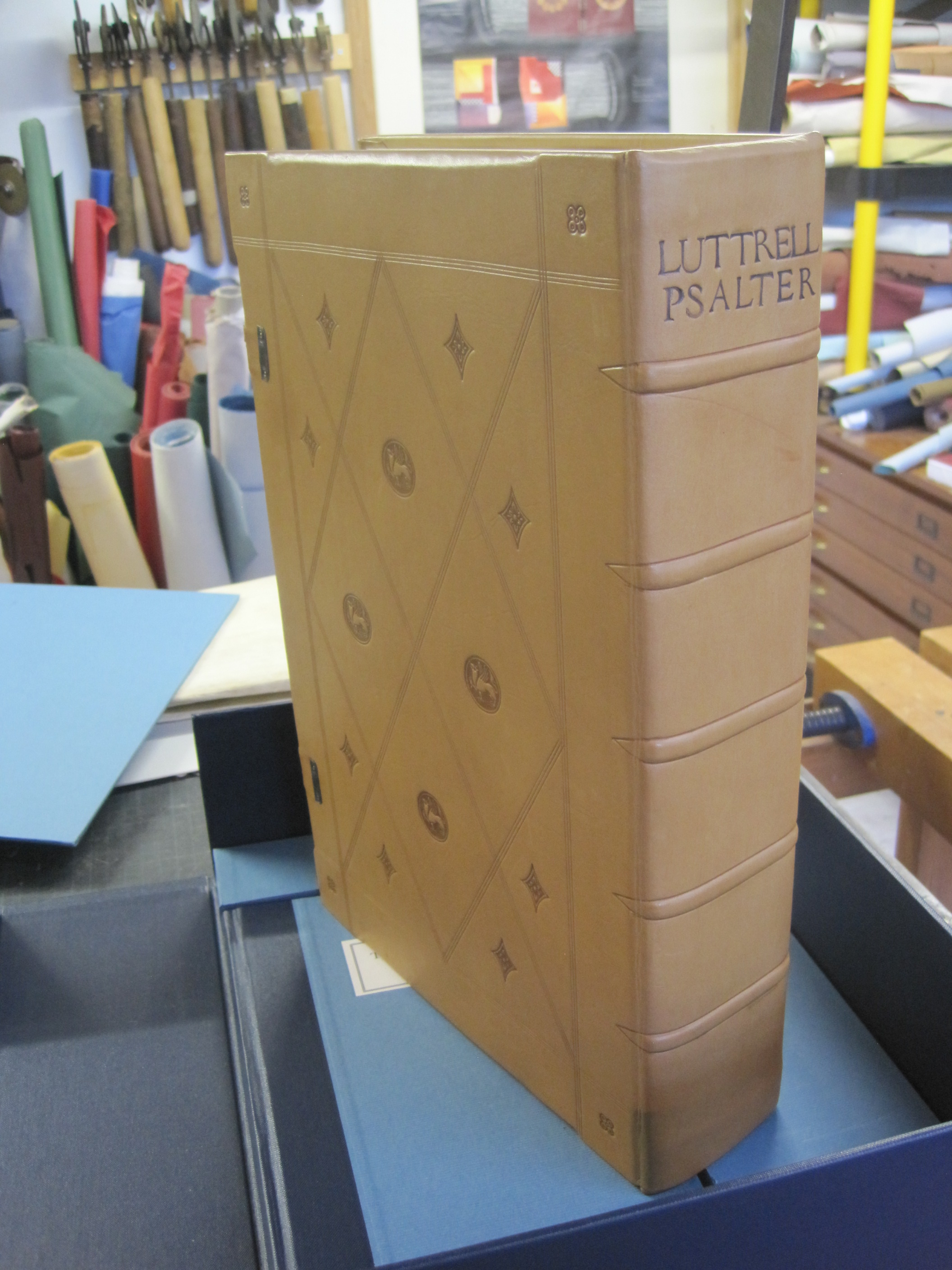

But I simply hate the design of the cover – bright blue morocco stamped with a gaudy imitation of medieval manuscript border decoration. So I determined to do better myself, using materials and decoration much more suited to the original, dating as it does from about 1340. Here are some ‘before and after’ pictures: the new binding is plain calf with blind tooling. The clasps are by Muller of Nussdorf, Germany (expensive, but very authentic copies of originals), the endpapers are real parchment.

Please share this post, or the whole blog, with others.

More to come!