It often happens that an old book has become distorted through use or neglect. If it is to be repaired satisfactorily the text has to be re-shaped so that head and tail are square and the back and foredge are neatly and evenly rounded. This can of course be achieved by separating all the sections, cleaning off the backs of the folds and re-sewing, but that is expensive – at least a couple of hours’ work for an ordinary octavo.

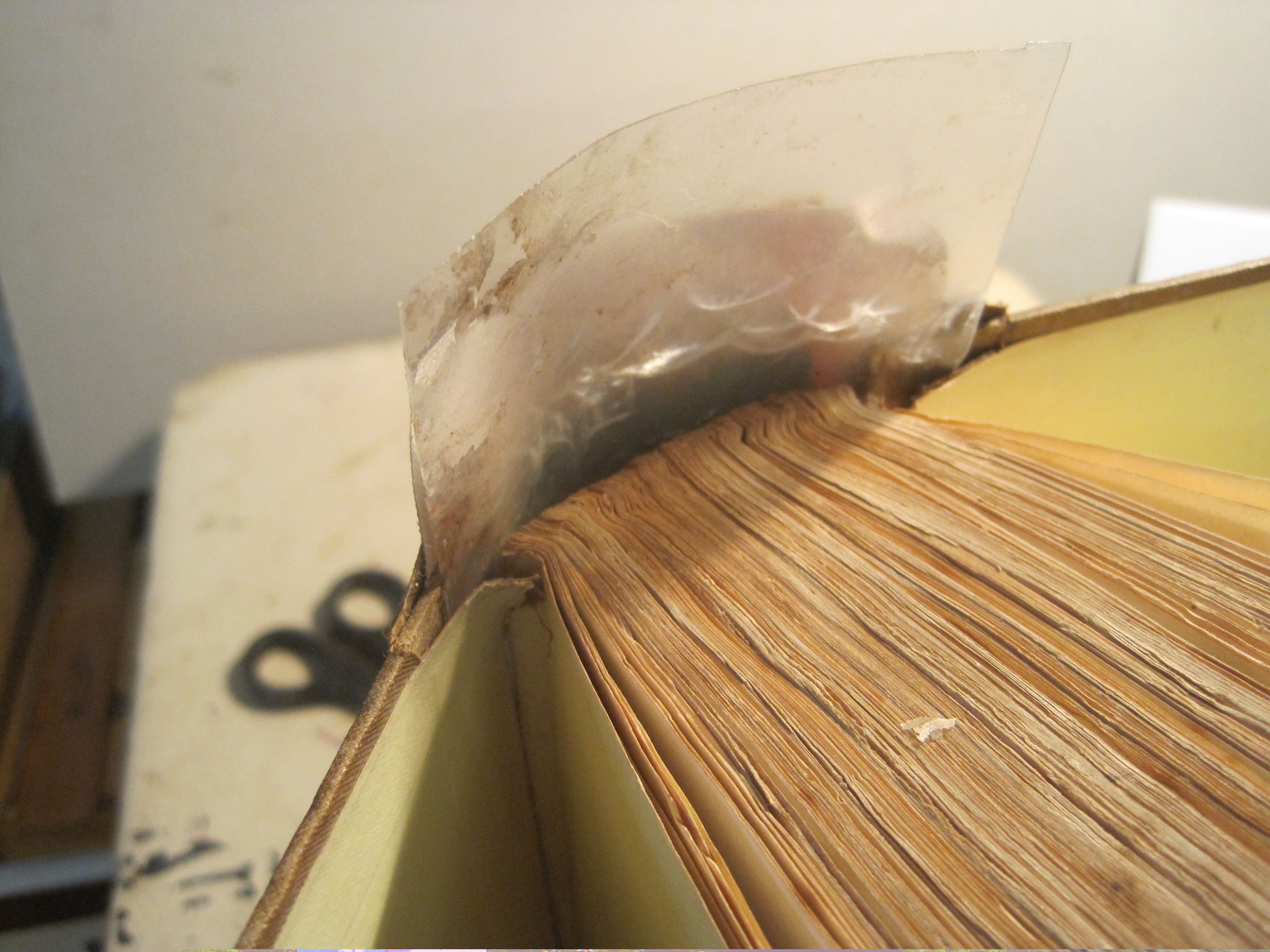

Quite often it is found that the sewing is pretty sound, merely a bit loose and that the distortion is caused by the spine linings being cracked and partly separated from the text. As stated in earlier posts, old back linings should be removed dry where possible, and that is greatly helped if the paper liner is scraped off first and then the mull-and-glue layer sharply tapped all over with the back edge of a lifting knife. This cracks the dry old glue away from the backs of the sections, enabling it, with the old mull which will certainly be weak if not rotten, to be picked off.

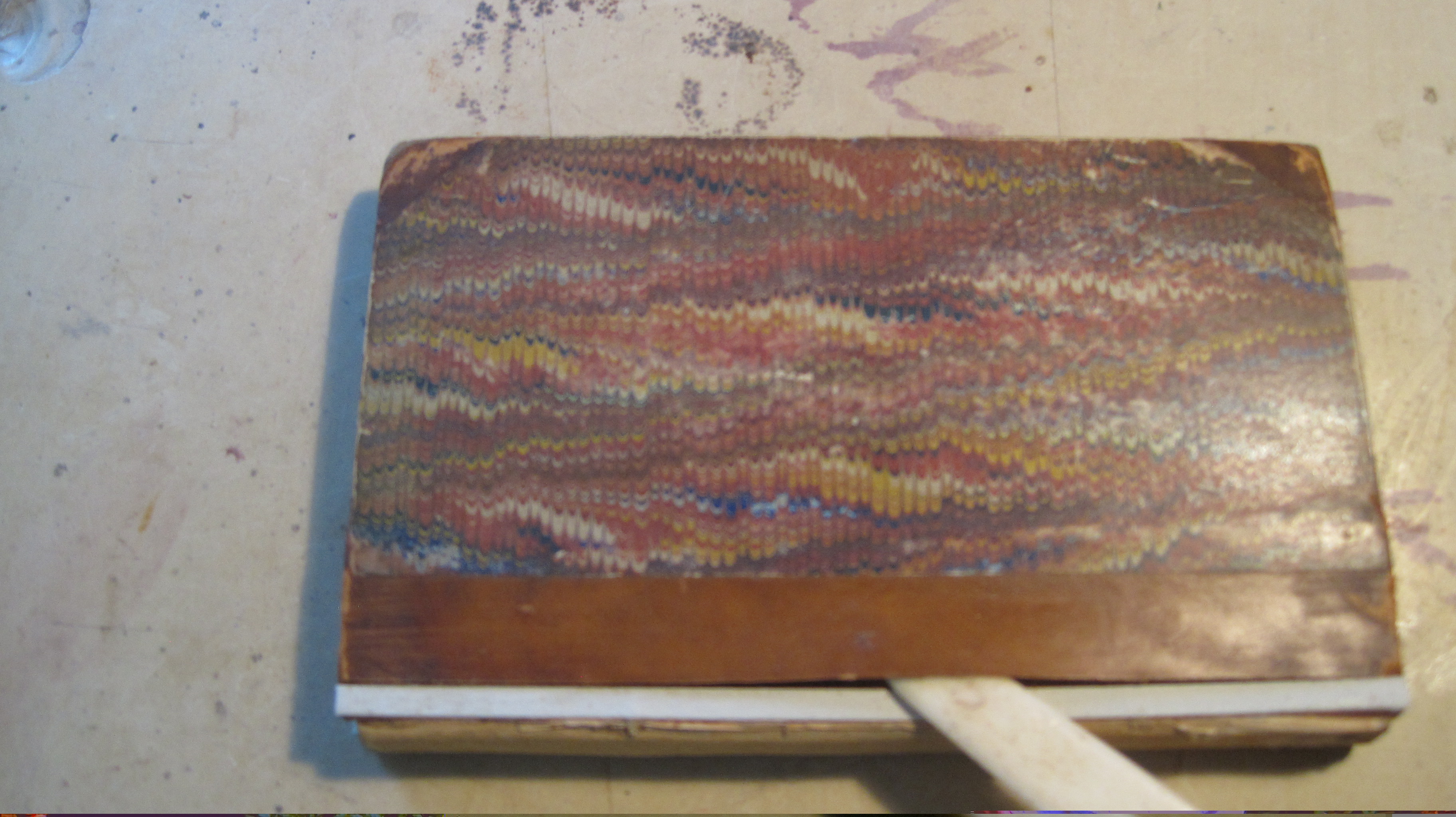

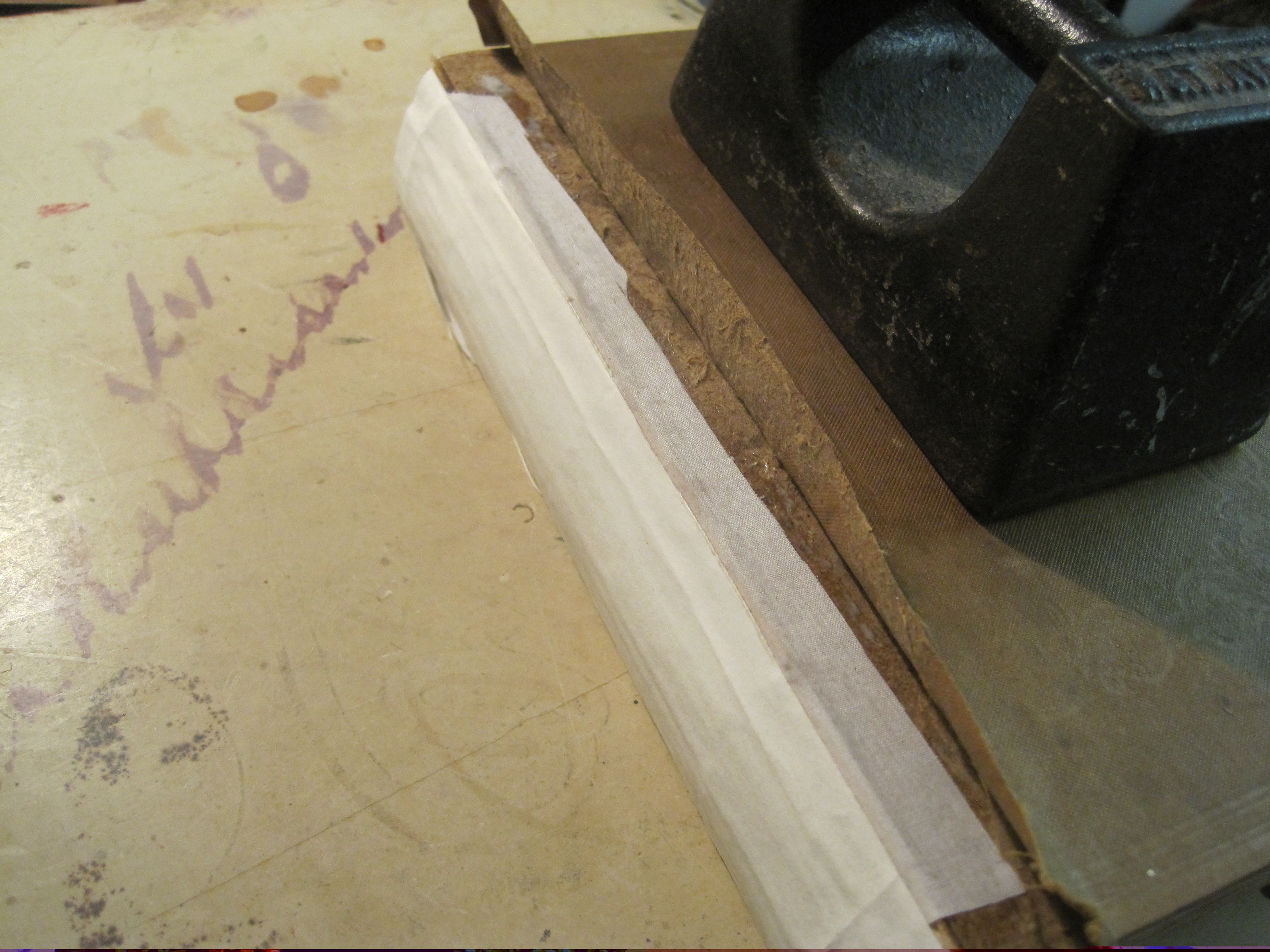

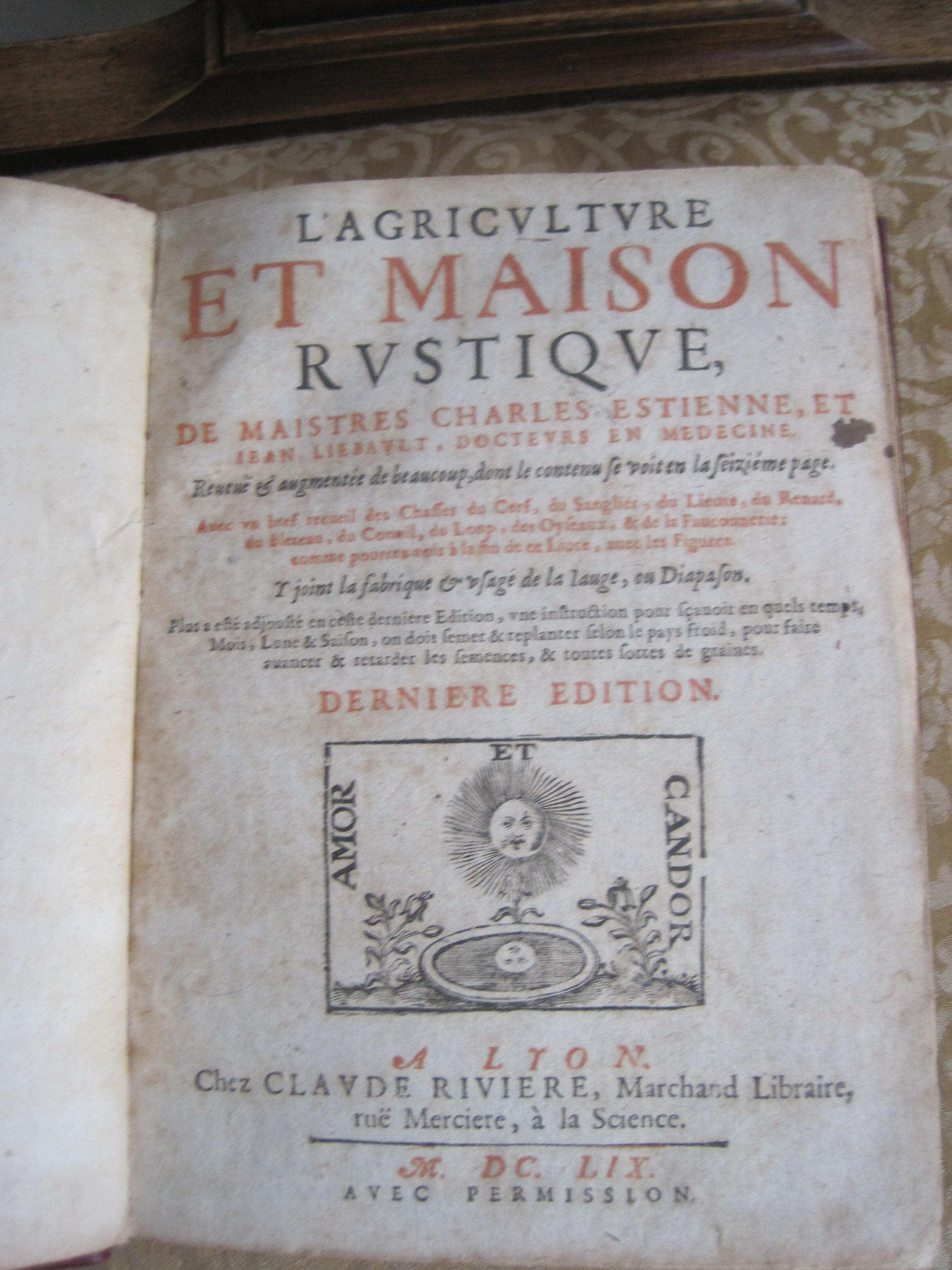

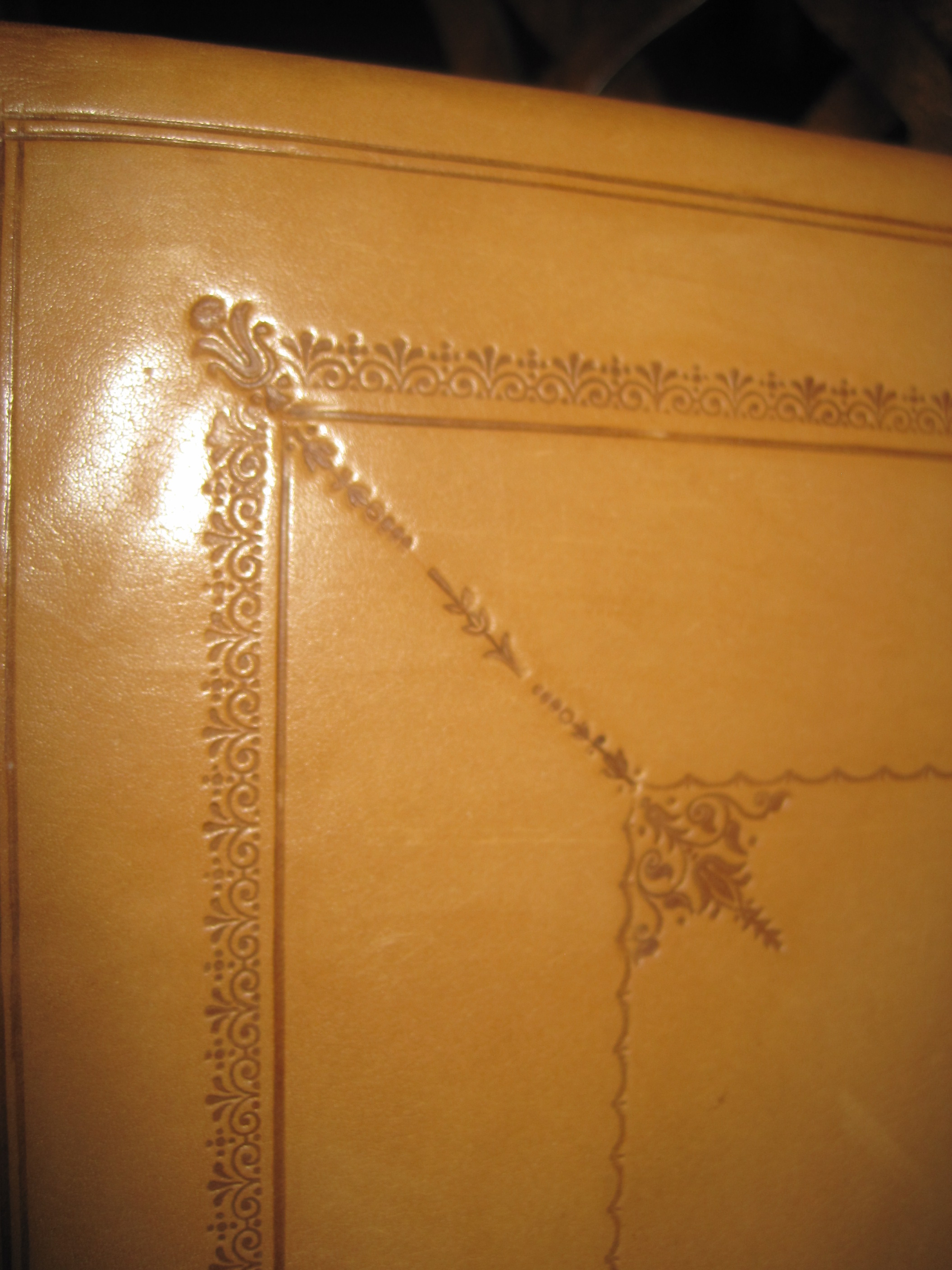

This picture shows the back after most of the lining has been removed.

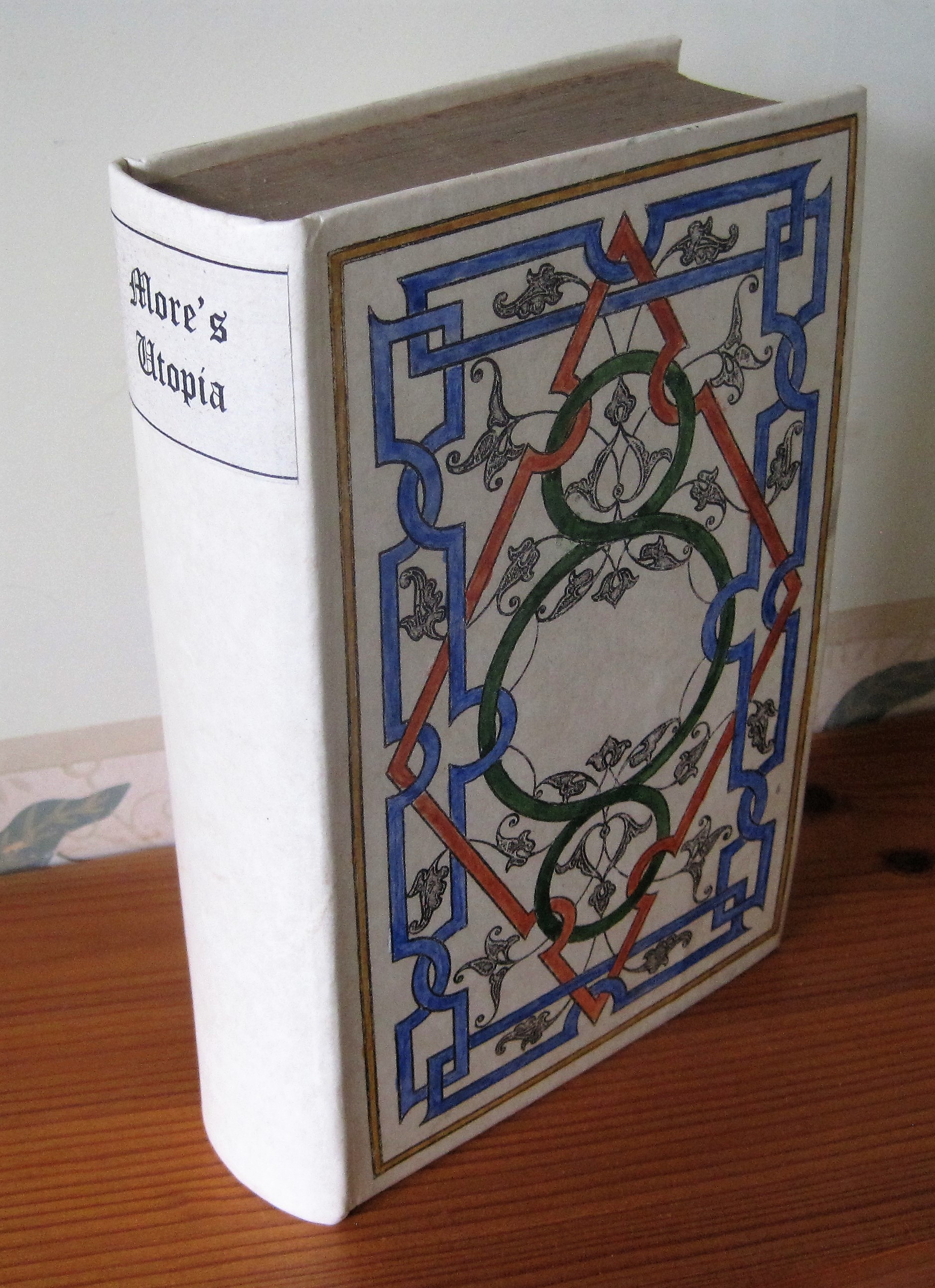

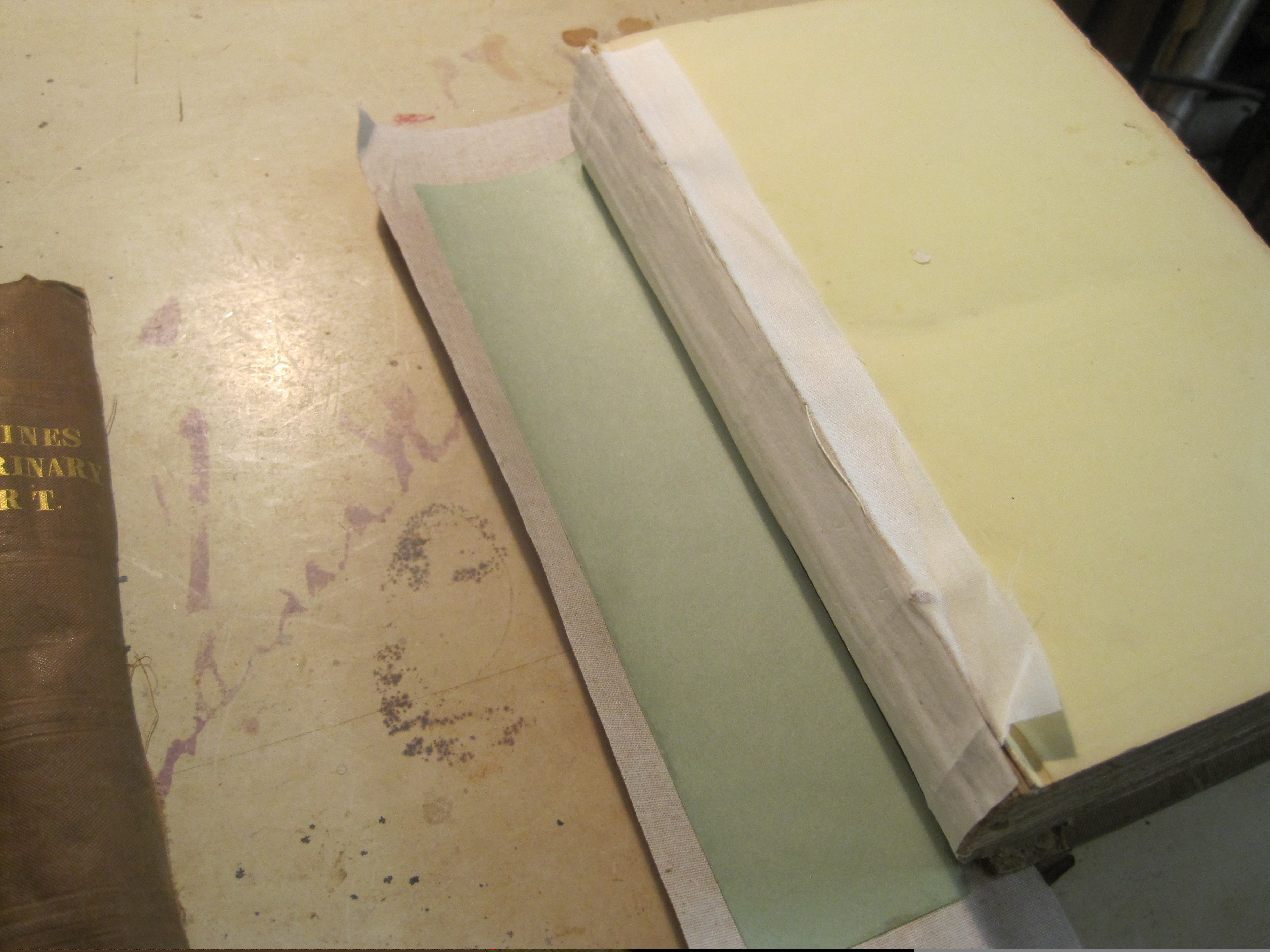

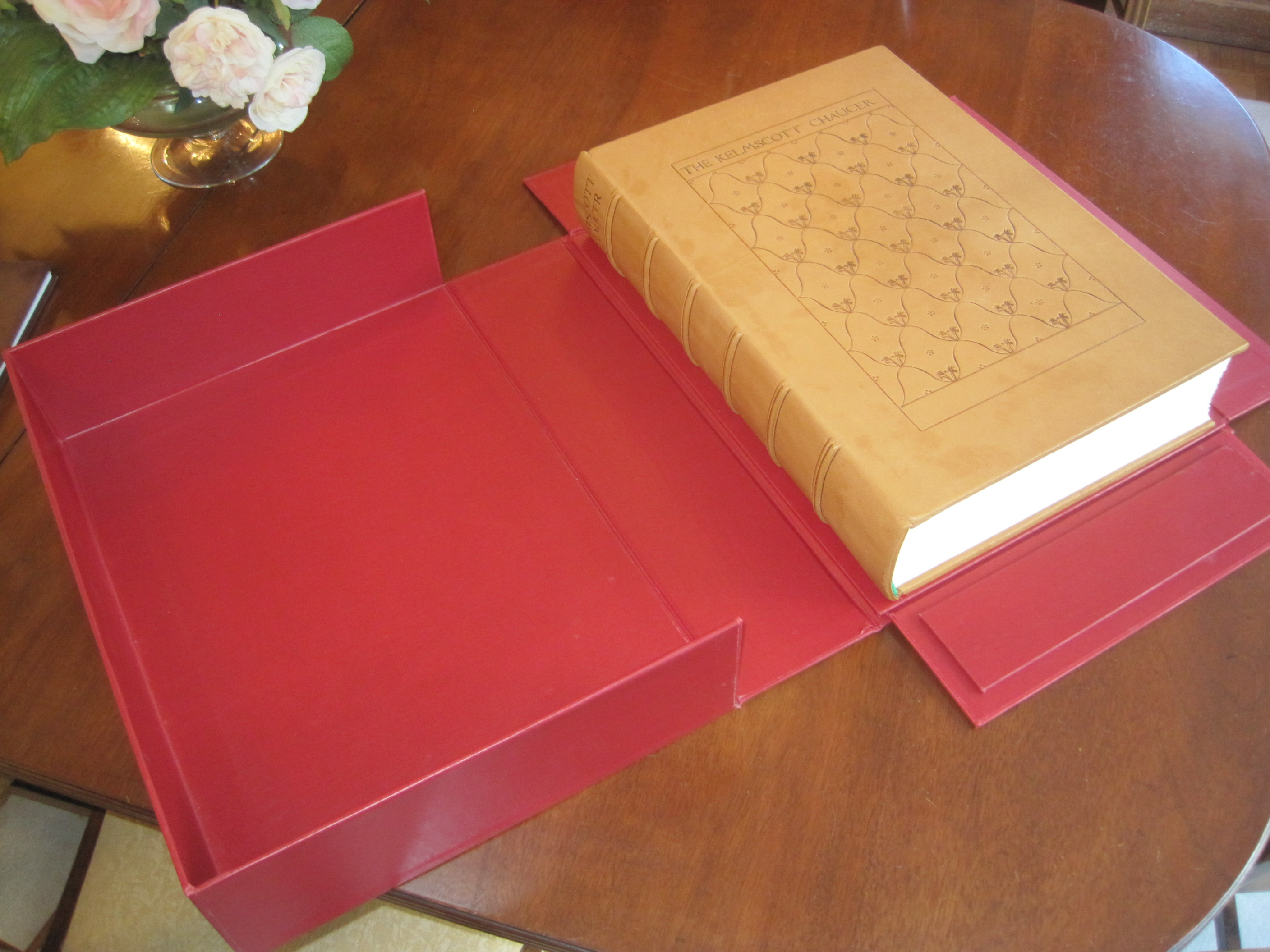

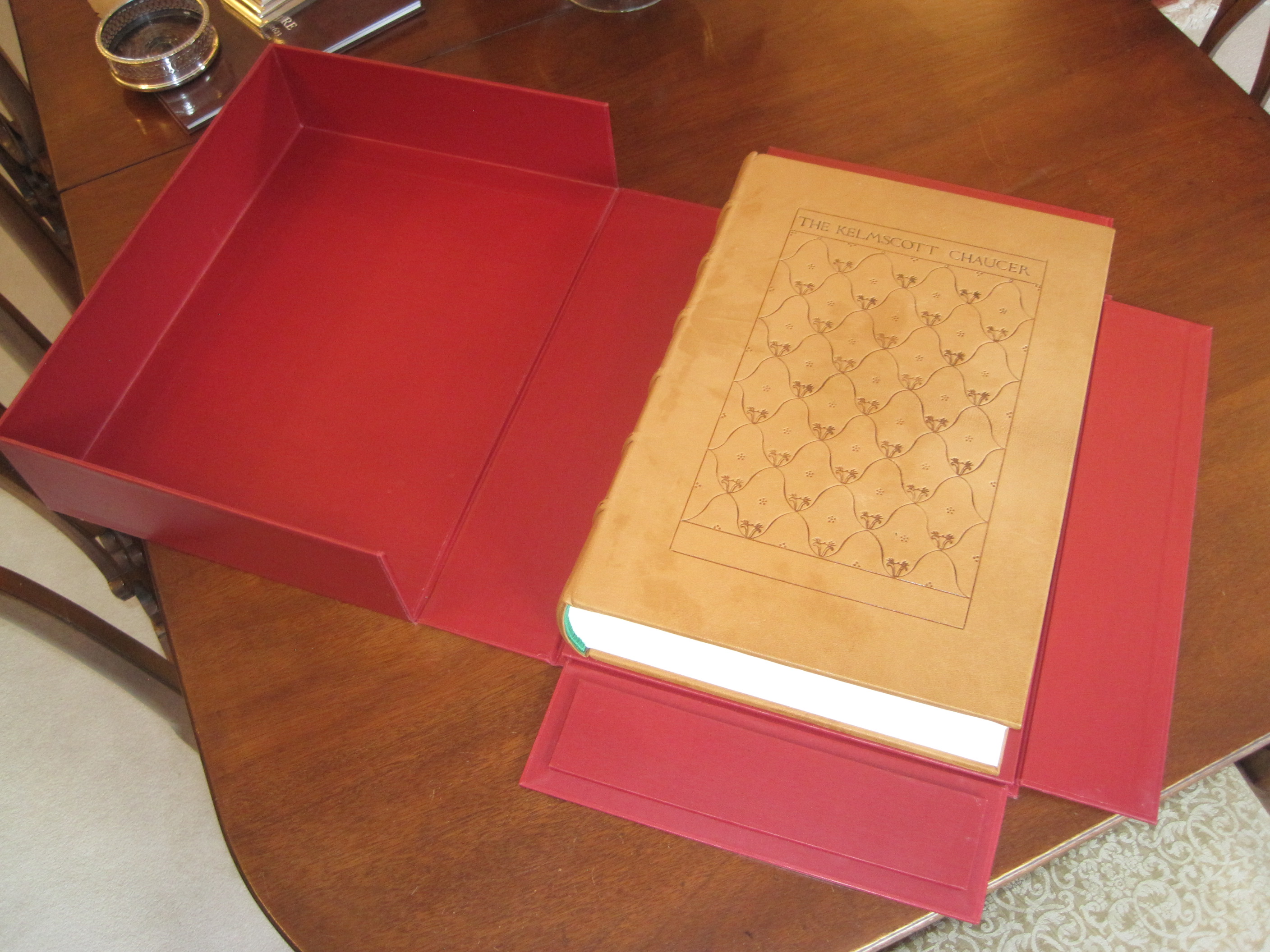

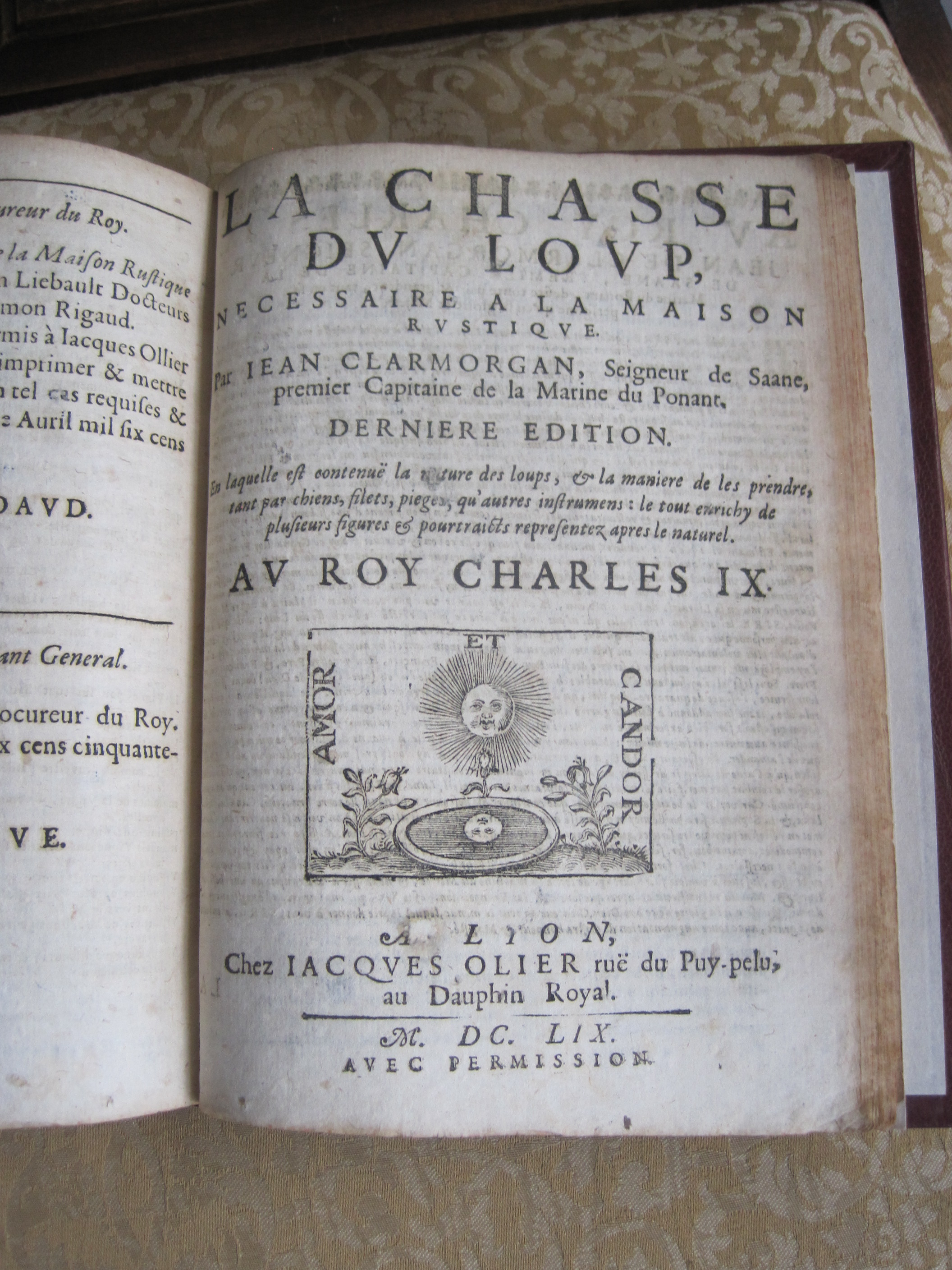

The problem now is to re-position the sections so none are indented at the back and therefore sticking out at the foredge, and to give the back a nice even round. It can be done by manipulation with the fingers but it’s a lot easier to put a section of plastic gutter under a finishing press and press the book down and wriggle it till it forms a smooth shape, at the same time evening up the head and tail, thus:

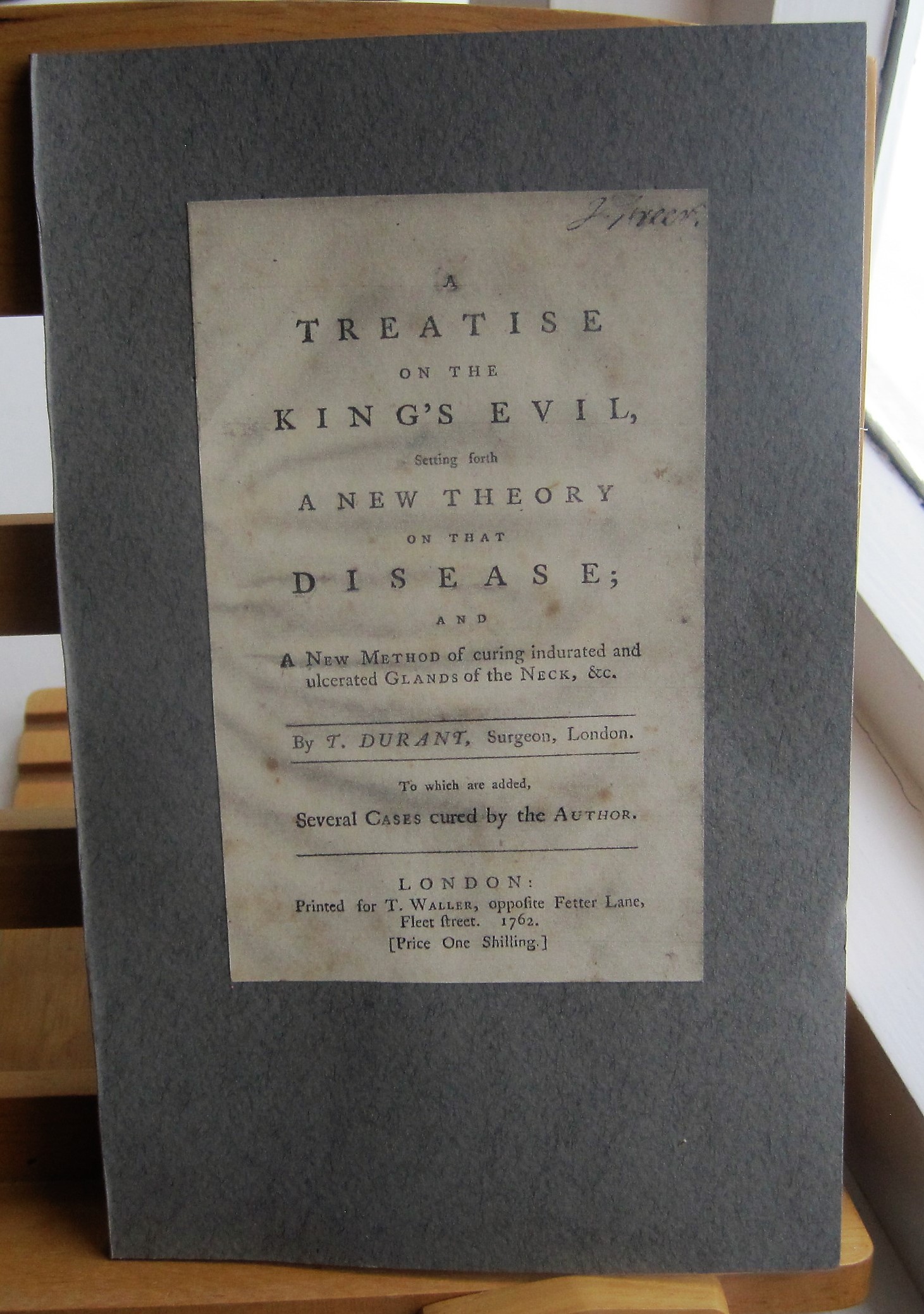

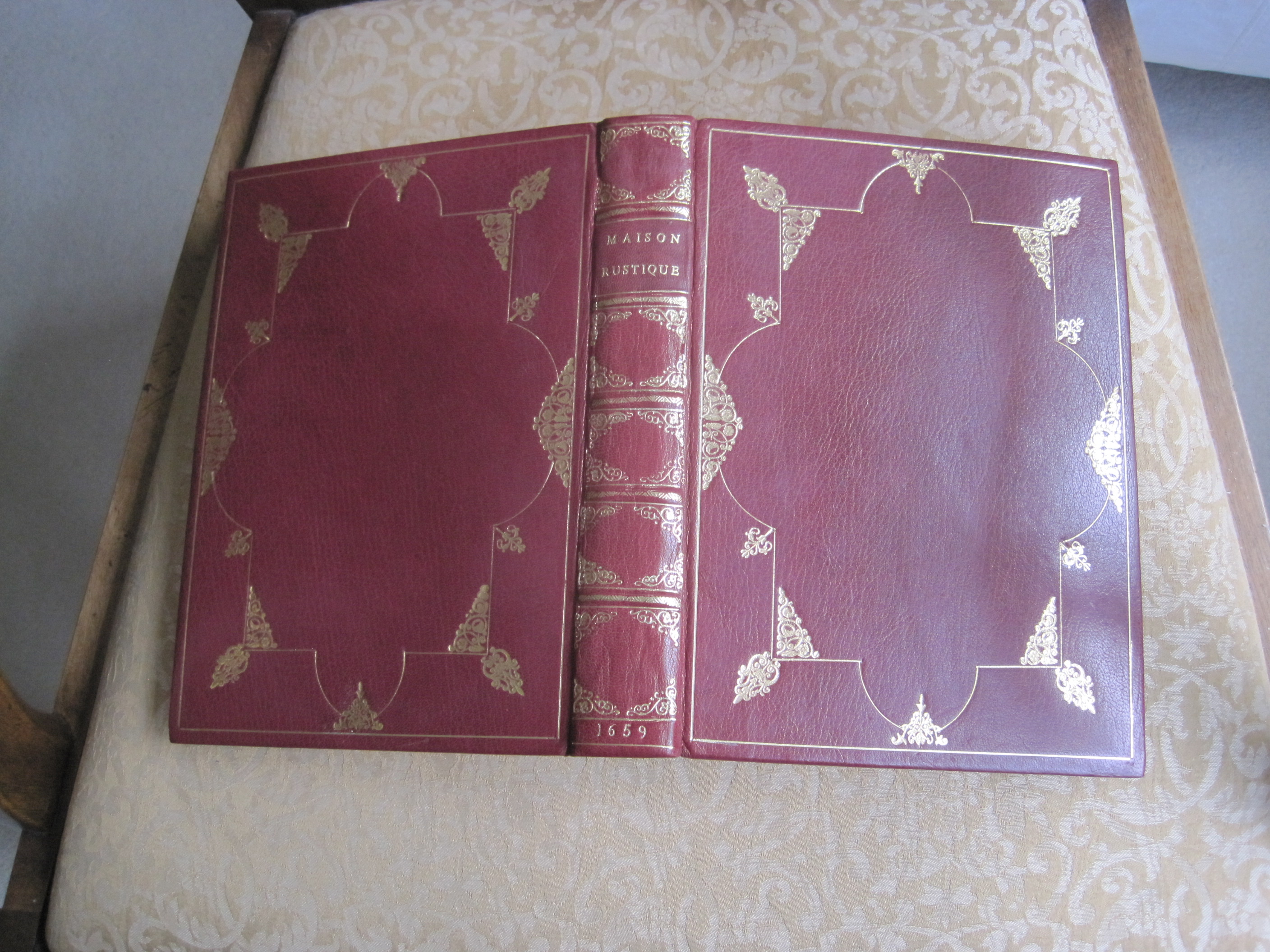

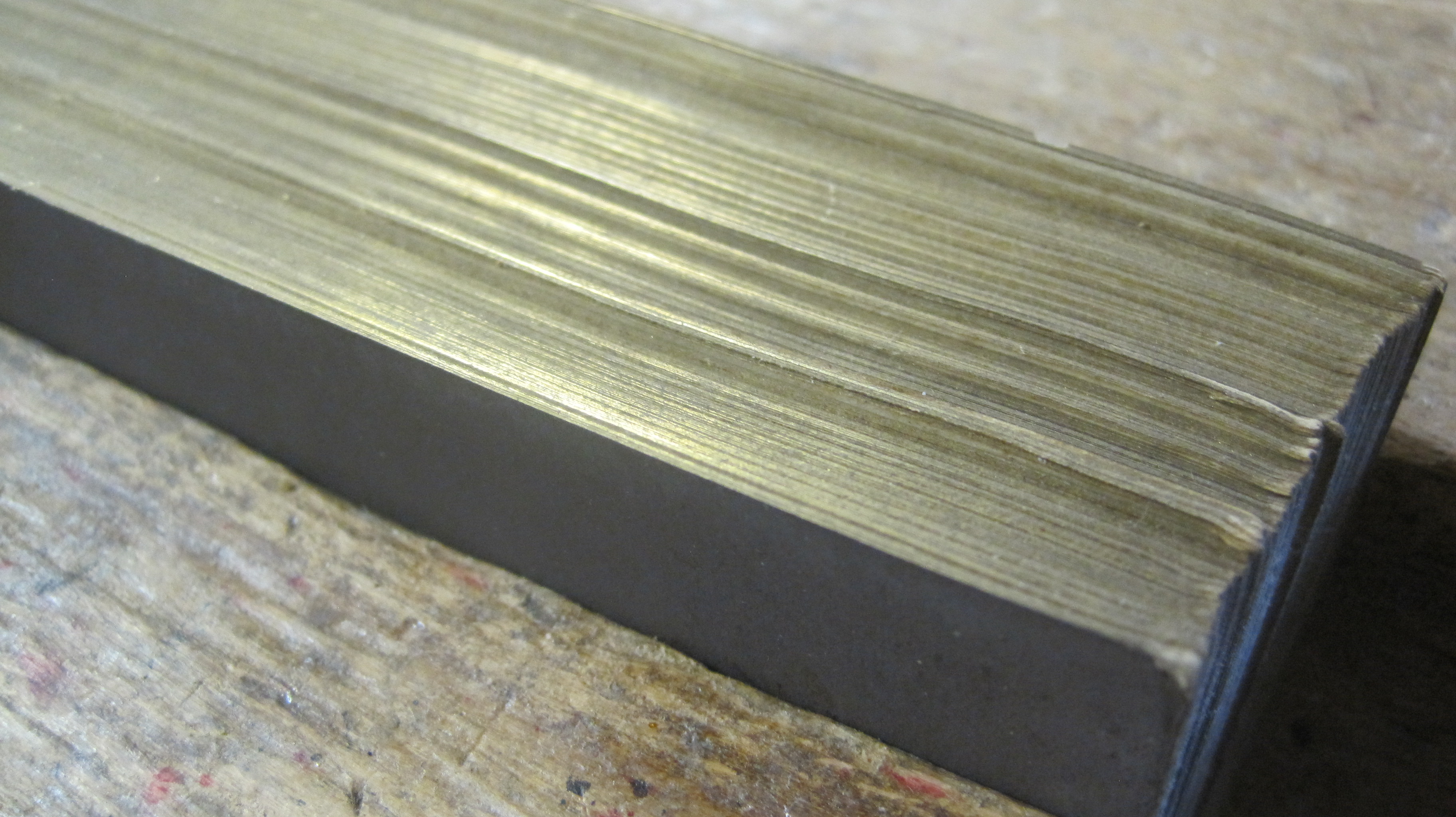

Compare the picture above with this, the foredge before re-shaping:

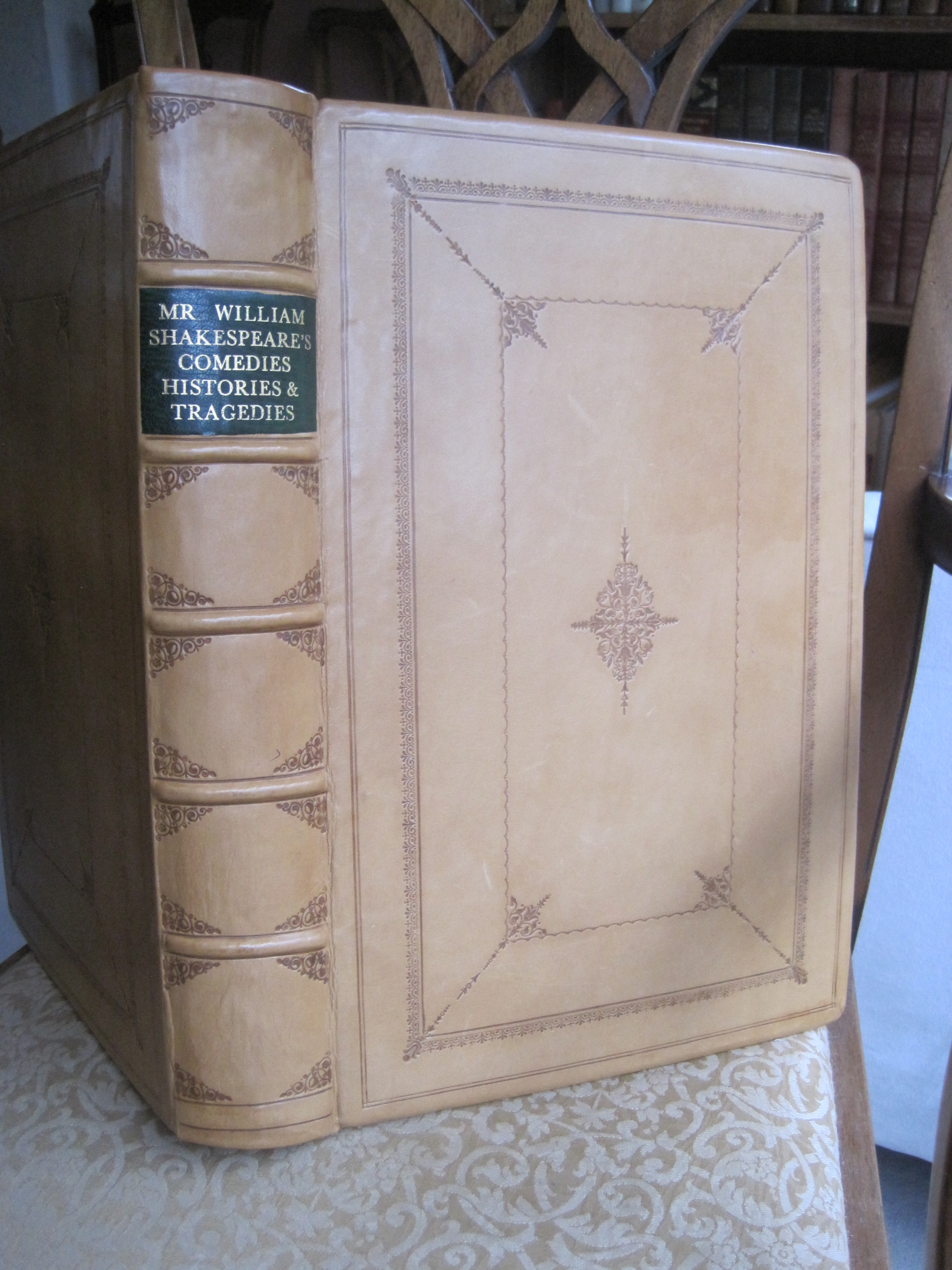

With the re-shaped book still in the finishing press, tighten it up and glue the back to set the new shape, sharpen the backing joints a bit and proceed to re-back as shown my earlier ‘Bread and butter stuff..’ post. The work has taken barely half an hour so far.